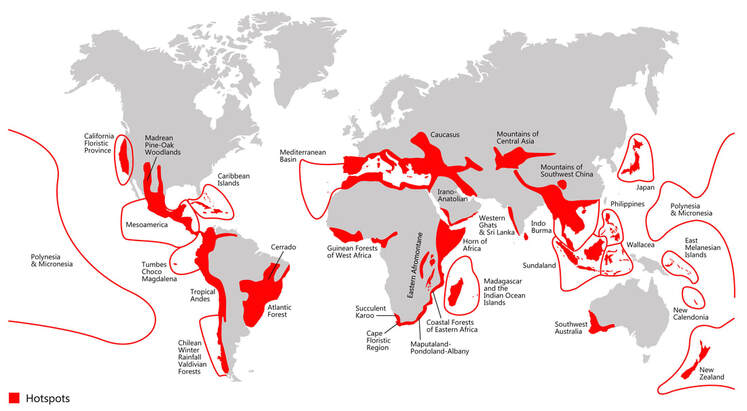

A biodiversity hotspot is a biogeographic region that is both a significant reservoir of biodiversity and is threatened with destruction. The term biodiversity hotspot specifically refers to biologically rich areas around the world that have lost at least 70 percent of their original habitat. The remaining natural habitat in these biodiversity hotspots amounts to just over two percent of the land surface of the planet, yet supports nearly 60 percent of the world's plant, bird, mammal, reptile, and amphibian species.

Biodiversity hotspots must have at least 1,500 vascular plants as endemics — which is to say, it must have a high percentage of plant life found nowhere else on the planet. A hotspot, in other words, is irreplaceable. It must have 30% or less of its original natural vegetation. In other words, it must be threatened. Around the world, 35 areas qualify as hotspots. They support more than half of the world’s plant species as endemics — i.e., species found no place else — and nearly 43% of bird, mammal, reptile and amphibian species as endemics.

They are not merely repositories of species; they play crucial roles in maintaining ecosystem services, such as pollination, water purification, and climate regulation. The essay explores the interconnectedness of species within hotspots and their contribution to global ecological balance. Understanding the ecological and evolutionary processes that contribute to the richness of biodiversity hotspots is vital for effective conservation strategies. Despite their ecological significance, biodiversity hotspots face numerous threats, including habitat destruction, climate change, invasive species, and overexploitation. This section assesses the anthropogenic and natural factors that jeopardize the existence of these critical areas.

Effective conservation strategies for biodiversity hotspots involve a combination of habitat protection, restoration efforts, community engagement, and sustainable resource management. The essay explores successful conservation initiatives and emphasizes the importance of global collaboration in preserving these unique ecosystems.

Biodiversity hotspots must have at least 1,500 vascular plants as endemics — which is to say, it must have a high percentage of plant life found nowhere else on the planet. A hotspot, in other words, is irreplaceable. It must have 30% or less of its original natural vegetation. In other words, it must be threatened. Around the world, 35 areas qualify as hotspots. They support more than half of the world’s plant species as endemics — i.e., species found no place else — and nearly 43% of bird, mammal, reptile and amphibian species as endemics.

They are not merely repositories of species; they play crucial roles in maintaining ecosystem services, such as pollination, water purification, and climate regulation. The essay explores the interconnectedness of species within hotspots and their contribution to global ecological balance. Understanding the ecological and evolutionary processes that contribute to the richness of biodiversity hotspots is vital for effective conservation strategies. Despite their ecological significance, biodiversity hotspots face numerous threats, including habitat destruction, climate change, invasive species, and overexploitation. This section assesses the anthropogenic and natural factors that jeopardize the existence of these critical areas.

Effective conservation strategies for biodiversity hotspots involve a combination of habitat protection, restoration efforts, community engagement, and sustainable resource management. The essay explores successful conservation initiatives and emphasizes the importance of global collaboration in preserving these unique ecosystems.

Myers (2000). Biodiversity hotspots for conservation priorities. Nature 403: 853–858

Impact of Climate Change on Biodiversity Hotspots

One of the primary impacts of climate change on biodiversity hotspots is the shifting distribution of plant and animal species. Rising temperatures and changing precipitation patterns force species to migrate to higher elevations or latitudes in search of suitable climate conditions. This movement can disrupt existing ecological communities and species interactions, leading to potential declines in biodiversity and changes in ecosystem functioning.

Climate change exacerbates habitat loss and degradation in biodiversity hotspots through phenomena such as wildfires, droughts, and storms. These extreme weather events can destroy habitats and fragment ecosystems, threatening the survival of endemic species adapted to specific environmental conditions. Habitat loss increases the risk of species extinctions and reduces overall biodiversity within these critical regions.

Changes in climate conditions can disrupt ecological processes and ecosystem dynamics within biodiversity hotspots. For example, alterations in temperature and precipitation regimes may affect the timing of flowering and fruiting in plant species, impacting pollinators and seed dispersers. These disruptions can have cascading effects on food webs and trophic interactions, further exacerbating the loss of biodiversity.

Endemic species within biodiversity hotspots are particularly vulnerable to the impacts of climate change due to their restricted ranges and specialized habitat requirements. Species with limited dispersal abilities may be unable to migrate to more suitable habitats, leading to local extinctions and loss of genetic diversity. The increased vulnerability of endemic species poses a significant threat to the overall biodiversity of these regions.

Climate change threatens to accelerate the loss of biodiversity within biodiversity hotspots by increasing the rate of species extinctions and reducing overall species richness. Loss of biodiversity can have far-reaching consequences for ecosystem functioning, resilience, and the provision of ecosystem services to human societies. Preserving biodiversity in these regions is essential for maintaining the health and stability of global ecosystems.

Climate change poses significant challenges for conservation efforts in biodiversity hotspots. Adaptive management strategies are needed to mitigate its impacts, including facilitating species movement and range expansion, restoring degraded habitats, and enhancing ecosystem resilience to climate variability. These efforts require coordinated action at local, national, and global levels to address the complex and interconnected challenges posed by climate change.

Biogeographic Patterns in Biodiversity Hotspots

Biodiversity hotspots are regions characterized by exceptionally high levels of species richness and endemism, making them crucial for global biodiversity conservation. Biogeography, the study of the distribution of species and ecosystems, plays a fundamental role in understanding the patterns and processes that shape biodiversity hotspots.

Biogeographic patterns in biodiversity hotspots often reflect historical speciation events driven by geological and climatic processes. Isolation of populations due to geographic barriers such as mountains, rivers, or oceans can lead to genetic divergence and ultimately the formation of new species. Endemic species found exclusively in biodiversity hotspots often trace their evolutionary origins to such speciation events, highlighting the importance of historical biogeography in shaping current patterns of biodiversity.

Dispersal is another key factor influencing biogeographic patterns in biodiversity hotspots. Species may colonize new habitats through long-distance dispersal events, facilitated by natural mechanisms such as wind, water currents, or animal migrations. Human activities, such as trade and transportation, can also influence dispersal patterns by introducing species to new areas. Understanding dispersal dynamics is essential for predicting the spread of invasive species and assessing the connectivity of habitat patches within biodiversity hotspots.

While biodiversity hotspots are renowned for their high levels of species richness, they are also vulnerable to extinction events that can erode biodiversity over time. Human-induced factors such as habitat destruction, climate change, and invasive species pose significant threats to endemic species in biodiversity hotspots, leading to population declines and local extinctions. Extinction events reshape biogeographic patterns by removing species from ecosystems and altering species composition and distribution.

Biogeographic patterns in biodiversity hotspots have important implications for biodiversity conservation efforts. Understanding the historical processes that have shaped current patterns of biodiversity can inform conservation strategies aimed at preserving endemic species and protecting critical habitats. Conservation initiatives may focus on maintaining connectivity between habitat patches, restoring degraded ecosystems, and mitigating the impacts of human activities on biodiversity hotspots.

Conservation Genomics of Endemic Species in Biodiversity Hotspots

Biodiversity hotspots harbor unique assemblages of species, many of which are endemic and found nowhere else on Earth. These endemic species are often highly vulnerable to environmental disturbances and face increased risks of extinction. Within these hotspots, endemic species face numerous threats, including habitat loss, climate change, and fragmentation, which jeopardize their survival. Conservation genomics, an interdisciplinary field combining genomics and conservation biology, offers powerful tools for understanding the genetic basis of adaptation, population dynamics, and species conservation. This essay examines the pivotal role of conservation genomics in safeguarding endemic species in biodiversity hotspots, emphasizing its applications in assessing genomic diversity, population structure, gene flow, and informing conservation strategies.

Conservation genomics provides unprecedented insights into the genomic diversity of endemic species in biodiversity hotspots. By analyzing whole-genome sequences or single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), researchers can quantify levels of genetic variation within populations and identify genomic regions under selection. Understanding genomic diversity enables prioritization of genetically diverse populations for conservation, facilitating the preservation of adaptive potential and resilience to environmental change.

Genomic approaches allow researchers to elucidate the population structure of endemic species, revealing patterns of genetic differentiation and connectivity between populations. Population genomic analyses, such as admixture mapping and genomic clustering methods, help delineate distinct genetic clusters, identify hybridization events, and assess barriers to gene flow. Knowledge of population structure informs the design of conservation strategies, including the establishment of genetic reserves and translocation programs to enhance genetic exchange and maintain evolutionary processes.

Maintaining connectivity between populations is crucial for the long-term survival of endemic species in biodiversity hotspots. Conservation genomics offers tools to assess connectivity and gene flow across landscapes, guiding conservation planning and corridor design. Genomic data can estimate migration rates, detect signatures of recent or historical gene flow, and identify genomic regions associated with adaptive divergence. Understanding patterns of gene flow informs habitat restoration efforts and landscape management strategies aimed at enhancing connectivity and mitigating the impacts of habitat fragmentation.

Conservation genomics informs evidence-based conservation strategies tailored to the genomic needs of endemic species in biodiversity hotspots. Genomic data can identify Evolutionarily Significant Units (ESUs) which serve as targets for conservation actions. Genomic tools, such as genomic sequencing and association mapping, facilitate the identification of adaptive traits, the detection of genomic signatures of selection, and the assessment of genetic health. Integrating genomic information with ecological and demographic data enhances the efficacy of conservation planning and management, ensuring the long-term viability of endemic species in biodiversity hotspots.

The Role of Keystone Species in Biodiversity Hotspots

Within these hotspots, certain species play disproportionately influential roles in maintaining ecosystem structure, function, and stability. These species, known as keystone species, exert significant effects on biodiversity and ecosystem processes, making them essential components of biodiversity conservation efforts. This essay explores the critical role of keystone species in biodiversity hotspots, highlighting their ecological significance, interactions with other species, and implications for conservation strategies.

Keystone species are species whose presence and activities have a disproportionately large impact on the structure and function of their ecosystems. These species often exert indirect effects that cascade through ecological communities, influencing species diversity, abundance, and interactions. Keystone species can regulate population sizes of other species, modify habitats, and enhance ecosystem resilience to environmental disturbances. Their removal or decline can lead to dramatic changes in ecosystem structure and function, potentially resulting in biodiversity loss and ecosystem degradation.

Keystone species interact with a wide range of other species within biodiversity hotspots, shaping community dynamics and ecosystem processes. Predators, such as top carnivores or apex predators, are classic examples of keystone species that regulate prey populations and maintain biodiversity by preventing dominance of certain species. Similarly, ecosystem engineers, such as beavers or corals, create and modify habitats, providing resources and refuge for numerous other species. Mutualistic keystone species, such as pollinators or seed dispersers, facilitate interactions between plants and animals, promoting ecosystem stability and resilience.

The presence of keystone species in biodiversity hotspots underscores their importance for ecosystem health and resilience. Conservation strategies aimed at preserving biodiversity hotspots must prioritize the protection and restoration of keystone species and their habitats. This may involve establishing protected areas, implementing habitat management practices, and restoring key ecological processes. Additionally, conservation efforts should address threats to keystone species, such as habitat loss, overexploitation, and climate change, to ensure the continued functioning of ecosystems and the maintenance of biodiversity hotspots.

Numerous case studies showcase the importance of keystone species in biodiversity hotspots. From beavers sculpting wetland habitats to penguins shaping Antarctic marine ecosystems, these species exemplify the intricate web of interactions underpinning biodiversity hotspots' resilience. Each case underscores the irreplaceable role of keystone species in maintaining ecosystem health and supporting biodiversity. African elephants are keystone species in savanna ecosystems, where their browsing and grazing activities shape vegetation structure and create habitat for other species. Elephants promote biodiversity by creating clearings, dispersing seeds, and modifying habitats. Wolves are keystone species in North American and European forests, where they regulate prey populations and influence community dynamics. Their presence maintains ecosystem balance, prevents overgrazing, and promotes species diversity. Various primate species serve as keystone species in tropical rainforest ecosystems, contributing to seed dispersal, pollination, and nutrient cycling. Their presence influences forest regeneration, plant diversity, and ecosystem stability. Bees and other pollinators are keystone species in various ecosystems worldwide, facilitating plant reproduction and supporting diverse wildlife and human communities. Their role in pollination sustains ecosystem services and agricultural productivity. Coral reefs are biodiversity hotspots themselves, with coral species serving as keystone species within these ecosystems. Corals provide habitat, food, and shelter for numerous marine organisms, supporting reef biodiversity and resilience. And giant tortoises are keystone species in the Galápagos Islands, where their grazing activities influence plant community structure and ecosystem dynamics. Tortoises shape habitat availability and resource availability for other species, contributing to island biodiversity.

One of the primary impacts of climate change on biodiversity hotspots is the shifting distribution of plant and animal species. Rising temperatures and changing precipitation patterns force species to migrate to higher elevations or latitudes in search of suitable climate conditions. This movement can disrupt existing ecological communities and species interactions, leading to potential declines in biodiversity and changes in ecosystem functioning.

Climate change exacerbates habitat loss and degradation in biodiversity hotspots through phenomena such as wildfires, droughts, and storms. These extreme weather events can destroy habitats and fragment ecosystems, threatening the survival of endemic species adapted to specific environmental conditions. Habitat loss increases the risk of species extinctions and reduces overall biodiversity within these critical regions.

Changes in climate conditions can disrupt ecological processes and ecosystem dynamics within biodiversity hotspots. For example, alterations in temperature and precipitation regimes may affect the timing of flowering and fruiting in plant species, impacting pollinators and seed dispersers. These disruptions can have cascading effects on food webs and trophic interactions, further exacerbating the loss of biodiversity.

Endemic species within biodiversity hotspots are particularly vulnerable to the impacts of climate change due to their restricted ranges and specialized habitat requirements. Species with limited dispersal abilities may be unable to migrate to more suitable habitats, leading to local extinctions and loss of genetic diversity. The increased vulnerability of endemic species poses a significant threat to the overall biodiversity of these regions.

Climate change threatens to accelerate the loss of biodiversity within biodiversity hotspots by increasing the rate of species extinctions and reducing overall species richness. Loss of biodiversity can have far-reaching consequences for ecosystem functioning, resilience, and the provision of ecosystem services to human societies. Preserving biodiversity in these regions is essential for maintaining the health and stability of global ecosystems.

Climate change poses significant challenges for conservation efforts in biodiversity hotspots. Adaptive management strategies are needed to mitigate its impacts, including facilitating species movement and range expansion, restoring degraded habitats, and enhancing ecosystem resilience to climate variability. These efforts require coordinated action at local, national, and global levels to address the complex and interconnected challenges posed by climate change.

Biogeographic Patterns in Biodiversity Hotspots

Biodiversity hotspots are regions characterized by exceptionally high levels of species richness and endemism, making them crucial for global biodiversity conservation. Biogeography, the study of the distribution of species and ecosystems, plays a fundamental role in understanding the patterns and processes that shape biodiversity hotspots.

Biogeographic patterns in biodiversity hotspots often reflect historical speciation events driven by geological and climatic processes. Isolation of populations due to geographic barriers such as mountains, rivers, or oceans can lead to genetic divergence and ultimately the formation of new species. Endemic species found exclusively in biodiversity hotspots often trace their evolutionary origins to such speciation events, highlighting the importance of historical biogeography in shaping current patterns of biodiversity.

Dispersal is another key factor influencing biogeographic patterns in biodiversity hotspots. Species may colonize new habitats through long-distance dispersal events, facilitated by natural mechanisms such as wind, water currents, or animal migrations. Human activities, such as trade and transportation, can also influence dispersal patterns by introducing species to new areas. Understanding dispersal dynamics is essential for predicting the spread of invasive species and assessing the connectivity of habitat patches within biodiversity hotspots.

While biodiversity hotspots are renowned for their high levels of species richness, they are also vulnerable to extinction events that can erode biodiversity over time. Human-induced factors such as habitat destruction, climate change, and invasive species pose significant threats to endemic species in biodiversity hotspots, leading to population declines and local extinctions. Extinction events reshape biogeographic patterns by removing species from ecosystems and altering species composition and distribution.

Biogeographic patterns in biodiversity hotspots have important implications for biodiversity conservation efforts. Understanding the historical processes that have shaped current patterns of biodiversity can inform conservation strategies aimed at preserving endemic species and protecting critical habitats. Conservation initiatives may focus on maintaining connectivity between habitat patches, restoring degraded ecosystems, and mitigating the impacts of human activities on biodiversity hotspots.

Conservation Genomics of Endemic Species in Biodiversity Hotspots

Biodiversity hotspots harbor unique assemblages of species, many of which are endemic and found nowhere else on Earth. These endemic species are often highly vulnerable to environmental disturbances and face increased risks of extinction. Within these hotspots, endemic species face numerous threats, including habitat loss, climate change, and fragmentation, which jeopardize their survival. Conservation genomics, an interdisciplinary field combining genomics and conservation biology, offers powerful tools for understanding the genetic basis of adaptation, population dynamics, and species conservation. This essay examines the pivotal role of conservation genomics in safeguarding endemic species in biodiversity hotspots, emphasizing its applications in assessing genomic diversity, population structure, gene flow, and informing conservation strategies.

Conservation genomics provides unprecedented insights into the genomic diversity of endemic species in biodiversity hotspots. By analyzing whole-genome sequences or single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), researchers can quantify levels of genetic variation within populations and identify genomic regions under selection. Understanding genomic diversity enables prioritization of genetically diverse populations for conservation, facilitating the preservation of adaptive potential and resilience to environmental change.

Genomic approaches allow researchers to elucidate the population structure of endemic species, revealing patterns of genetic differentiation and connectivity between populations. Population genomic analyses, such as admixture mapping and genomic clustering methods, help delineate distinct genetic clusters, identify hybridization events, and assess barriers to gene flow. Knowledge of population structure informs the design of conservation strategies, including the establishment of genetic reserves and translocation programs to enhance genetic exchange and maintain evolutionary processes.

Maintaining connectivity between populations is crucial for the long-term survival of endemic species in biodiversity hotspots. Conservation genomics offers tools to assess connectivity and gene flow across landscapes, guiding conservation planning and corridor design. Genomic data can estimate migration rates, detect signatures of recent or historical gene flow, and identify genomic regions associated with adaptive divergence. Understanding patterns of gene flow informs habitat restoration efforts and landscape management strategies aimed at enhancing connectivity and mitigating the impacts of habitat fragmentation.

Conservation genomics informs evidence-based conservation strategies tailored to the genomic needs of endemic species in biodiversity hotspots. Genomic data can identify Evolutionarily Significant Units (ESUs) which serve as targets for conservation actions. Genomic tools, such as genomic sequencing and association mapping, facilitate the identification of adaptive traits, the detection of genomic signatures of selection, and the assessment of genetic health. Integrating genomic information with ecological and demographic data enhances the efficacy of conservation planning and management, ensuring the long-term viability of endemic species in biodiversity hotspots.

The Role of Keystone Species in Biodiversity Hotspots

Within these hotspots, certain species play disproportionately influential roles in maintaining ecosystem structure, function, and stability. These species, known as keystone species, exert significant effects on biodiversity and ecosystem processes, making them essential components of biodiversity conservation efforts. This essay explores the critical role of keystone species in biodiversity hotspots, highlighting their ecological significance, interactions with other species, and implications for conservation strategies.

Keystone species are species whose presence and activities have a disproportionately large impact on the structure and function of their ecosystems. These species often exert indirect effects that cascade through ecological communities, influencing species diversity, abundance, and interactions. Keystone species can regulate population sizes of other species, modify habitats, and enhance ecosystem resilience to environmental disturbances. Their removal or decline can lead to dramatic changes in ecosystem structure and function, potentially resulting in biodiversity loss and ecosystem degradation.

Keystone species interact with a wide range of other species within biodiversity hotspots, shaping community dynamics and ecosystem processes. Predators, such as top carnivores or apex predators, are classic examples of keystone species that regulate prey populations and maintain biodiversity by preventing dominance of certain species. Similarly, ecosystem engineers, such as beavers or corals, create and modify habitats, providing resources and refuge for numerous other species. Mutualistic keystone species, such as pollinators or seed dispersers, facilitate interactions between plants and animals, promoting ecosystem stability and resilience.

The presence of keystone species in biodiversity hotspots underscores their importance for ecosystem health and resilience. Conservation strategies aimed at preserving biodiversity hotspots must prioritize the protection and restoration of keystone species and their habitats. This may involve establishing protected areas, implementing habitat management practices, and restoring key ecological processes. Additionally, conservation efforts should address threats to keystone species, such as habitat loss, overexploitation, and climate change, to ensure the continued functioning of ecosystems and the maintenance of biodiversity hotspots.

Numerous case studies showcase the importance of keystone species in biodiversity hotspots. From beavers sculpting wetland habitats to penguins shaping Antarctic marine ecosystems, these species exemplify the intricate web of interactions underpinning biodiversity hotspots' resilience. Each case underscores the irreplaceable role of keystone species in maintaining ecosystem health and supporting biodiversity. African elephants are keystone species in savanna ecosystems, where their browsing and grazing activities shape vegetation structure and create habitat for other species. Elephants promote biodiversity by creating clearings, dispersing seeds, and modifying habitats. Wolves are keystone species in North American and European forests, where they regulate prey populations and influence community dynamics. Their presence maintains ecosystem balance, prevents overgrazing, and promotes species diversity. Various primate species serve as keystone species in tropical rainforest ecosystems, contributing to seed dispersal, pollination, and nutrient cycling. Their presence influences forest regeneration, plant diversity, and ecosystem stability. Bees and other pollinators are keystone species in various ecosystems worldwide, facilitating plant reproduction and supporting diverse wildlife and human communities. Their role in pollination sustains ecosystem services and agricultural productivity. Coral reefs are biodiversity hotspots themselves, with coral species serving as keystone species within these ecosystems. Corals provide habitat, food, and shelter for numerous marine organisms, supporting reef biodiversity and resilience. And giant tortoises are keystone species in the Galápagos Islands, where their grazing activities influence plant community structure and ecosystem dynamics. Tortoises shape habitat availability and resource availability for other species, contributing to island biodiversity.

|

Case Studies: Southeast Asia

Rich in wildlife, Southeast Asia includes at least six of the world’s 25 biodiversity hotspots – the areas of the world that contain an exceptional concentration of species, and are exceptionally endangered. The region contains 20% of the planet’s vertebrate and plant species and the world’s third-largest tropical forest. In addition to this existing biodiversity, the region has an extraordinary rate of species discovery, with more than 2,216 new species described between 1997 and 2014 alone. Global comparisons are difficult but it seems the Mekong region has a higher rate of species discovery than other parts of the tropics, with hundreds of new species described annually. Unfortunately, deforestation rates in Southeast Asia are some of the highest anywhere on Earth, and the rate of mining is the highest in the tropics. The region also has a number of hydropower dams under construction and consumption of species for traditional medicines is particularly pronounced - both of which contribute to elimination of habitat which can be particularly problematic for species with small ranges. The only critically endangered hornbills, the rufous-headed hornbill and the Sulu hornbill, are restricted to the Philippines. The latter species is one of the world's rarest birds, with only 20 breeding pairs or 40 mature individuals, and faces imminent extinction. The Ticao hornbill, a subspecies of the Visayan hornbill, is probably already extinct. Tropical forests and savannas account for more than 60 percent of global net primary productivity and 40 percent of carbon storage, respectively. But the tropics face an assortment of well-documented human-driven threats: destruction of forests and marine ecosystems, over-exploitation by industrial fishing fleets and commercial hunters, the spread of diseases and invasive species, and the growing impacts of climate change, which stress both ecosystems and their inhabitants. |

|

These threats, which often interact and build on each other, are heightening the risk of extinction for many species. Already, the vast majority of recorded extinctions among five major vertebrate groups assessed by the IUCN occurred among tropical species. These threats aren’t likely to diminish soon. Human population continues to rise, but growing affluence means that it is increasingly outpaced by resource consumption, which acts a multiplier in terms of humanity’s planetary footprint.

Western Ghats, India

Biodiversity Significance: The Western Ghats, a mountain range in India, is recognized as one of the world's biodiversity hotspots. It harbors a remarkable variety of species, including numerous endemic plants, amphibians, and mammals.

Threats: Rapid urbanization, agricultural expansion, and infrastructure development have posed severe threats to the Western Ghats. Deforestation and habitat fragmentation disrupt ecological corridors, affecting the movement of species.

Conservation Initiatives: The creation of protected areas, such as the Nilgiri Biosphere Reserve, has been a key conservation strategy. Additionally, community-based initiatives, involving local populations in sustainable resource management, have shown promise in reducing anthropogenic pressures on the region's ecosystems.

Madagascar

Biodiversity Significance: Madagascar is an island nation known for its extraordinary level of endemism, with a high percentage of species found nowhere else on Earth. Lemurs, chameleons, and diverse plant species contribute to its unique biodiversity.

Threats: Deforestation due to slash-and-burn agriculture, logging, and mining activities pose significant threats to Madagascar's biodiversity. The island's isolation makes its ecosystems particularly vulnerable to habitat loss.

Conservation Initiatives: Conservation International's work in Madagascar highlights the importance of community involvement. Projects promoting sustainable agriculture and agroforestry have sought to balance human needs with conservation goals. Protected areas, such as Ranomafana National Park, showcase the effectiveness of habitat preservation in safeguarding endemic species.

The Atlantic Forest, Brazil

Biodiversity Significance: The Atlantic Forest, one of the most threatened biodiversity hotspots globally, is characterized by high endemism and diverse ecosystems. It once covered a vast area along the Brazilian coast but has been drastically reduced to small, fragmented patches.

Threats: Deforestation, agriculture expansion, urbanization, and logging have significantly reduced the extent of the Atlantic Forest. Fragmentation isolates populations, leading to genetic bottlenecks and increased vulnerability to invasive species.

Conservation Initiatives: Conservation International's work in the Atlantic Forest includes the establishment of the Guapi Assu Biological Reserve and the promotion of Payment for Ecosystem Services (PES) programs. These initiatives aim to protect remaining habitats, restore degraded areas, and provide economic incentives for local communities to engage in sustainable land-use practices.

The Coral Triangle, Southeast Asia

Biodiversity Significance: The Coral Triangle, spanning the seas of Indonesia, Malaysia, Papua New Guinea, the Philippines, Solomon Islands, and Timor-Leste, is a marine biodiversity hotspot. It is renowned for its high coral diversity, hosting over 75% of the world's coral species.

Threats: Overfishing, destructive fishing practices, climate change, and pollution pose significant threats to the Coral Triangle. Coral bleaching, driven by rising sea temperatures, jeopardizes the health of marine ecosystems.

Conservation Initiatives: The Coral Triangle Initiative (CTI) is a collaborative effort among six countries to address common challenges in marine conservation. It focuses on sustainable fisheries management, marine protected areas, and climate change adaptation. Local initiatives, such as community-based marine reserves, empower communities to actively participate in conservation and sustainable resource use.

Biodiversity Significance: The Western Ghats, a mountain range in India, is recognized as one of the world's biodiversity hotspots. It harbors a remarkable variety of species, including numerous endemic plants, amphibians, and mammals.

Threats: Rapid urbanization, agricultural expansion, and infrastructure development have posed severe threats to the Western Ghats. Deforestation and habitat fragmentation disrupt ecological corridors, affecting the movement of species.

Conservation Initiatives: The creation of protected areas, such as the Nilgiri Biosphere Reserve, has been a key conservation strategy. Additionally, community-based initiatives, involving local populations in sustainable resource management, have shown promise in reducing anthropogenic pressures on the region's ecosystems.

Madagascar

Biodiversity Significance: Madagascar is an island nation known for its extraordinary level of endemism, with a high percentage of species found nowhere else on Earth. Lemurs, chameleons, and diverse plant species contribute to its unique biodiversity.

Threats: Deforestation due to slash-and-burn agriculture, logging, and mining activities pose significant threats to Madagascar's biodiversity. The island's isolation makes its ecosystems particularly vulnerable to habitat loss.

Conservation Initiatives: Conservation International's work in Madagascar highlights the importance of community involvement. Projects promoting sustainable agriculture and agroforestry have sought to balance human needs with conservation goals. Protected areas, such as Ranomafana National Park, showcase the effectiveness of habitat preservation in safeguarding endemic species.

The Atlantic Forest, Brazil

Biodiversity Significance: The Atlantic Forest, one of the most threatened biodiversity hotspots globally, is characterized by high endemism and diverse ecosystems. It once covered a vast area along the Brazilian coast but has been drastically reduced to small, fragmented patches.

Threats: Deforestation, agriculture expansion, urbanization, and logging have significantly reduced the extent of the Atlantic Forest. Fragmentation isolates populations, leading to genetic bottlenecks and increased vulnerability to invasive species.

Conservation Initiatives: Conservation International's work in the Atlantic Forest includes the establishment of the Guapi Assu Biological Reserve and the promotion of Payment for Ecosystem Services (PES) programs. These initiatives aim to protect remaining habitats, restore degraded areas, and provide economic incentives for local communities to engage in sustainable land-use practices.

The Coral Triangle, Southeast Asia

Biodiversity Significance: The Coral Triangle, spanning the seas of Indonesia, Malaysia, Papua New Guinea, the Philippines, Solomon Islands, and Timor-Leste, is a marine biodiversity hotspot. It is renowned for its high coral diversity, hosting over 75% of the world's coral species.

Threats: Overfishing, destructive fishing practices, climate change, and pollution pose significant threats to the Coral Triangle. Coral bleaching, driven by rising sea temperatures, jeopardizes the health of marine ecosystems.

Conservation Initiatives: The Coral Triangle Initiative (CTI) is a collaborative effort among six countries to address common challenges in marine conservation. It focuses on sustainable fisheries management, marine protected areas, and climate change adaptation. Local initiatives, such as community-based marine reserves, empower communities to actively participate in conservation and sustainable resource use.

Solutions

1. Reduce personal and corporate ecological footprints

2. Mandate corporations realize negative externalities

3. Reimagine society

4) Half Earth, Rewild

5) Implement biodiversity protections into government policy at international, national, and local levels

6) Document biodiversity

Solutions

1. Reduce personal and corporate ecological footprints

2. Mandate corporations realize negative externalities

3. Reimagine society

4) Half Earth, Rewild

5) Implement biodiversity protections into government policy at international, national, and local levels

6) Document biodiversity

News and Resources

Colombia grants ‘historic’ protections to rainforest and indigenous groups. The move includes the addition of 8 million hectares (80,000 square kilometers or 31,000 square miles) to its protected areas - a 27% increase. And, grants indigenous communities the ability and autonomy to govern their own territories.

|

The Oriental Pied Hornbill (Anthracoceros albirostris), photographed in Khao Yai National Park, Thailand. Though not endangered, unlike several of its 54 other sister species, this one is nonetheless an incredible sight. The hornbills are a family of bird found in tropical and subtropical Africa, Asia and Melanesia. They commonly have a casque on the upper mandible which is a hollow structure that runs along the upper mandible. In some species it is barely perceptible and appears to serve no function beyond reinforcing the bill. In other species it is quite large, is reinforced with bone, resonating calls. In a couple of species, the casque is not hollow but is filled with hornbill ivory and is used as a battering ram in aerial jousts.

|

Photo credit: William Helenbrook

Photo credit: William Helenbrook

The Brown Basilisk, Basciliscus vittatus, is commonly known for its ability to “walk on water.” Traditionally they are found from northwestern Colombia up to Mexico; however, they have more recently made their home in Southern Florida. At first look, you might consider them to be descendants of dinosaurs - but you’d be wrong. More accurately, dinosaurs and lizards split off some 265 million years ago. The clade Sauria includes all reptiles -and birds. Travel through time - and the Archelosauria split off, forming the archosaurs. The archosaurs are a bit famous because they led to non-avian dinosaurs, modern-day birds, and crocodiles. Alternatively, the Lepidosauria led to snakes, lizards, and the tuatara. What’s a tuatara? From an evolutionary standpoint, they are exceptional. Why? They are the only living species left of the order Rhynchocephalia. You’d have to go back 200 million years to find a common ancestor of lizards and snakes. What’s also fascinating is that crocodiles are more closely related to birds (and dinosaurs) than they are to modern-day lizards. So, despite looking quite “dinosaur-like,” this Jesus Lizard is on his own evolutionary path. If you really want to see a dinosaur relative, look for some birds or find yourself a crocodile.

Photo credit: William Helenbrook

Photo credit: William Helenbrook

The Lemur Leaf Frog (Agalychnis lemur) is listed as Critically Endangered because of ongoing drastic population declines, estimated to be more than 80% over a ten year period, inferred from the apparent disappearance of most of the Costa Rican, and some of the western Panamanian, population, probably mostly due to chytridiomycosis. However, general habitat loss also remains a threat, and this is especially the case in Costa Rica where deforestation by squatters threatens one of the three known remaining populations. It was once considered to be a reasonably common species in Costa Rica, but most populations have recently disappeared. Within Costa Rica, the former range included several national parks and other protected areas; none of the remaining populations are within protected areas. The species is known to be present within at least six Panamanian protected areas, but it is not known from any protected areas in Colombia. A successful captive breeding program began in 2001 at the Atlanta Botanical Garden, which has since transferred individuals to other zoos to continue these captive breeding efforts. An ex-situ population of this species is breeding at the El Valle Amphibian Conservation Center in Panama. It is a nocturnal tree frog associated with sloping areas in humid lowland and montane primary forest, and is not found in degraded habitats. The eggs are usually deposited on leaf surfaces and the larvae are washed off or fall into water below the site of oviposition (IUCN).

Photo credit: William Helenbrook

Photo credit: William Helenbrook

The brown titi monkey (Callicebus brunneus). Though it is not facing imminent extinction, most primate populations are plummeting worldwide. In the most bleak assessment of primates to date, conservationists have found that 60% of wild species are on course to die out, with three-quarters already in steady decline.