A carbon footprint is defined as the total emissions caused by an individual, event, organisation, or product, expressed as carbon dioxide equivalent. Most of the carbon footprint emissions for the average U.S. household come from "indirect" sources, i.e. fuel burned to produce goods far away from the final consumer. These are distinguished from emissions which come from burning fuel directly in one's car or stove, commonly referred to as "direct" sources of the consumer's carbon footprint. Those countries with the largest footprint include the United States and China; however per capita measurements show a much different picture.

On pure emissions alone, the key points are:

• China emits more CO2 than the US and Canada put together - up by 171% since the year 2000

• The US has had declining CO2 for two years running, the last time the US had declining CO2 for 3 years running was in the 1980s

• The UK is down one place to tenth on the list, 8% on the year. The country is now behind Iran, South Korea, Japan and Germany

• India is now the world's third biggest emitter of CO2 - pushing Russia into fourth place

• The biggest decrease from 2008-2009 is Ukraine - down 28%. The biggest increase is the Cook Islands - up 66.7%

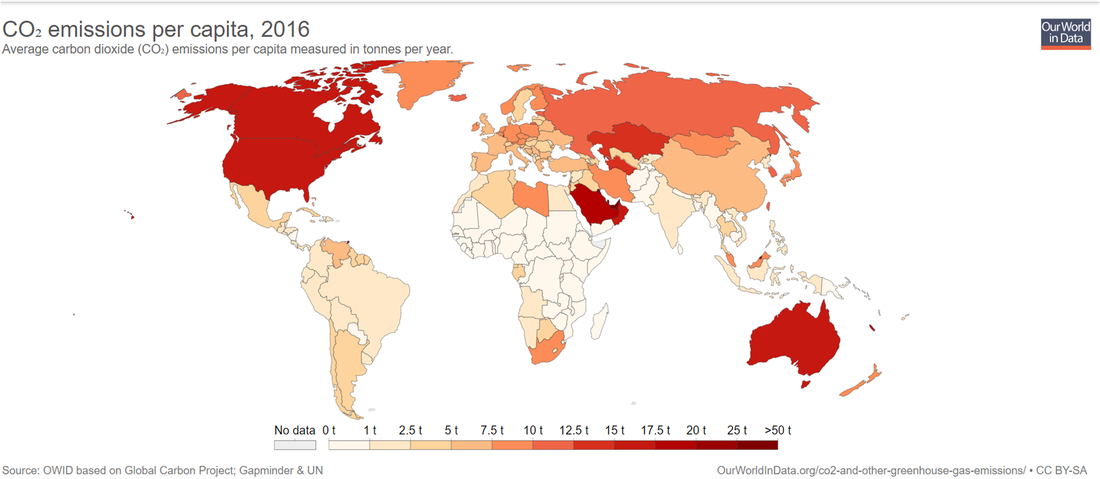

If you look at per capita emissions, a different picture emerges where:

• Some of the world's smallest countries and islands emit the most per person - the highest being Gibraltar with 152 tonnes per person

• The US is still number one in terms of per capita emissions among the big economies - with 18 tonnes emitted per person

• China, by contrast, emits under six tonnes per person, India only 1.38

• For comparison, the whole world emits 4.49 tonnes per person

• China emits more CO2 than the US and Canada put together - up by 171% since the year 2000

• The US has had declining CO2 for two years running, the last time the US had declining CO2 for 3 years running was in the 1980s

• The UK is down one place to tenth on the list, 8% on the year. The country is now behind Iran, South Korea, Japan and Germany

• India is now the world's third biggest emitter of CO2 - pushing Russia into fourth place

• The biggest decrease from 2008-2009 is Ukraine - down 28%. The biggest increase is the Cook Islands - up 66.7%

If you look at per capita emissions, a different picture emerges where:

• Some of the world's smallest countries and islands emit the most per person - the highest being Gibraltar with 152 tonnes per person

• The US is still number one in terms of per capita emissions among the big economies - with 18 tonnes emitted per person

• China, by contrast, emits under six tonnes per person, India only 1.38

• For comparison, the whole world emits 4.49 tonnes per person

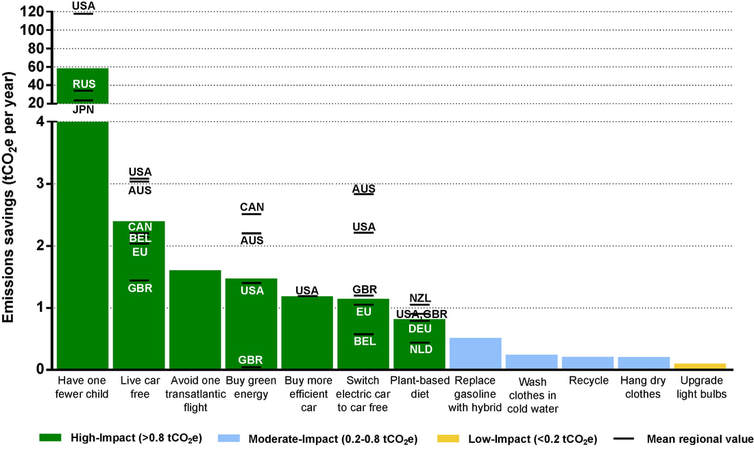

The top four ways to reduce your impact on the planet: eat a plant-based diet, avoid air travel, live car free, and have a smaller family.

Lifestyle is not one but two orders of magnitude more important than population numbers for greenhouse gas emissions.

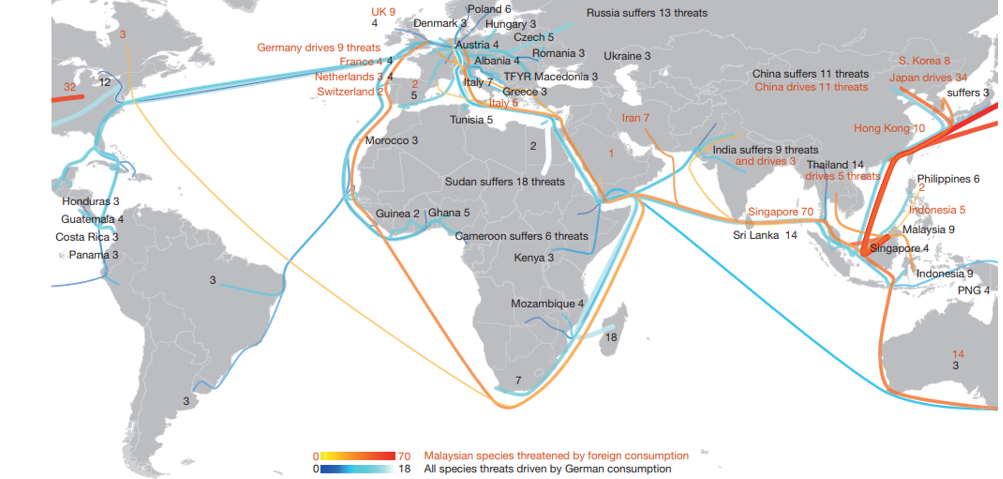

Human activities are causing Earth’s sixth major extinction event: an accelerating decline of the world’s stocks of biological diversity at rates 100 to 1,000 times pre-human levels. Historically, low-impact intrusion into species habitats arose from local demands for food, fuel and living space. However, in today’s increasingly globalized economy, international trade chains accelerate habitat degradation far removed from the place of consumption.

Many studies have linked export-intensive industries with biodiversity threats, for example, coffee growing in Mexico and Latin America, soya and beef production in Brazil, forestry and fishing in Papua New Guinea, palm oil plantations in Indonesia and Malaysia, and ornamental fish catching in Vietnam, to name but a few.

Many studies have linked export-intensive industries with biodiversity threats, for example, coffee growing in Mexico and Latin America, soya and beef production in Brazil, forestry and fishing in Papua New Guinea, palm oil plantations in Indonesia and Malaysia, and ornamental fish catching in Vietnam, to name but a few.

Local threats to species are driven by economic activity and consumer demand across the world (Lenzen 2012). Consequently, policy aimed at reducing local threats to species should be designed from a global perspective, taking into account not just the local producers who directly degrade and destroy habitat but also the consumers who benefit from the degradation and destruction.

Allocating responsibility between producers and consumers is not straightforward. Producers exert the impacts and control production methods, but consumer choice and demand drives production, so that responsibility may lie with both camps, and should have to be shared between them. The consumer responsibility principle is now receiving ample attention in the climate change debate. Its political relevance is demonstrated by China’s official stance that final consumer countries should be held accountable for the greenhouse gases emitted during the production of China’s export goods.

Ending with consumers, environmental labels such as advertising dolphin-safe canned tuna, organic produce and fair trade coffee have

been a well-known sight for decades. Although these examples refer to relative short, intuitively traceable supply chains, there is in principle

no obstacle to extending such labeling and certification to more complex international trade routes. This is demonstrated by the United

Kingdom’s Carbon Reduction Label, which despite shortcomings requires the quantification of a product’s full carbon footprint. Given the complete equivalence of carbon and biodiversity footprinting methodologies, integration of species Red Lists with global trade databases could provide a starting point for more comprehensive biodiversity labeling schemes. However, whether sustainability-minded consumers and shareholders can be a force in mitigating the impacts they drive will depend on whether sustainability certification schemes will be able to overcome their current limited efficacy.

Allocating responsibility between producers and consumers is not straightforward. Producers exert the impacts and control production methods, but consumer choice and demand drives production, so that responsibility may lie with both camps, and should have to be shared between them. The consumer responsibility principle is now receiving ample attention in the climate change debate. Its political relevance is demonstrated by China’s official stance that final consumer countries should be held accountable for the greenhouse gases emitted during the production of China’s export goods.

Ending with consumers, environmental labels such as advertising dolphin-safe canned tuna, organic produce and fair trade coffee have

been a well-known sight for decades. Although these examples refer to relative short, intuitively traceable supply chains, there is in principle

no obstacle to extending such labeling and certification to more complex international trade routes. This is demonstrated by the United

Kingdom’s Carbon Reduction Label, which despite shortcomings requires the quantification of a product’s full carbon footprint. Given the complete equivalence of carbon and biodiversity footprinting methodologies, integration of species Red Lists with global trade databases could provide a starting point for more comprehensive biodiversity labeling schemes. However, whether sustainability-minded consumers and shareholders can be a force in mitigating the impacts they drive will depend on whether sustainability certification schemes will be able to overcome their current limited efficacy.

Resources

The climate mitigation gap - education and government recommendations miss the most effective individual actions; Lenzen, M., et al. (2012). International trade drives biodiversity threats in developing nations. Nature, 486(7401), 109.

Gold Standard for Global Goals

The climate mitigation gap - education and government recommendations miss the most effective individual actions; Lenzen, M., et al. (2012). International trade drives biodiversity threats in developing nations. Nature, 486(7401), 109.

Gold Standard for Global Goals