Biodiversity Loss and the Extinction Crisis

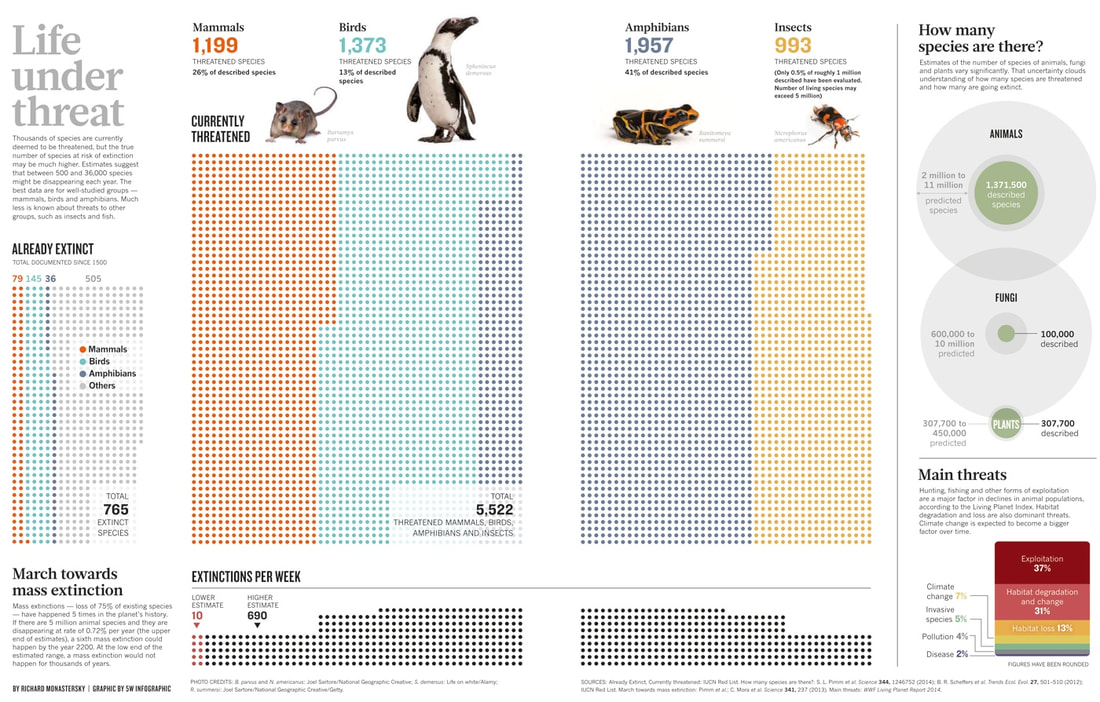

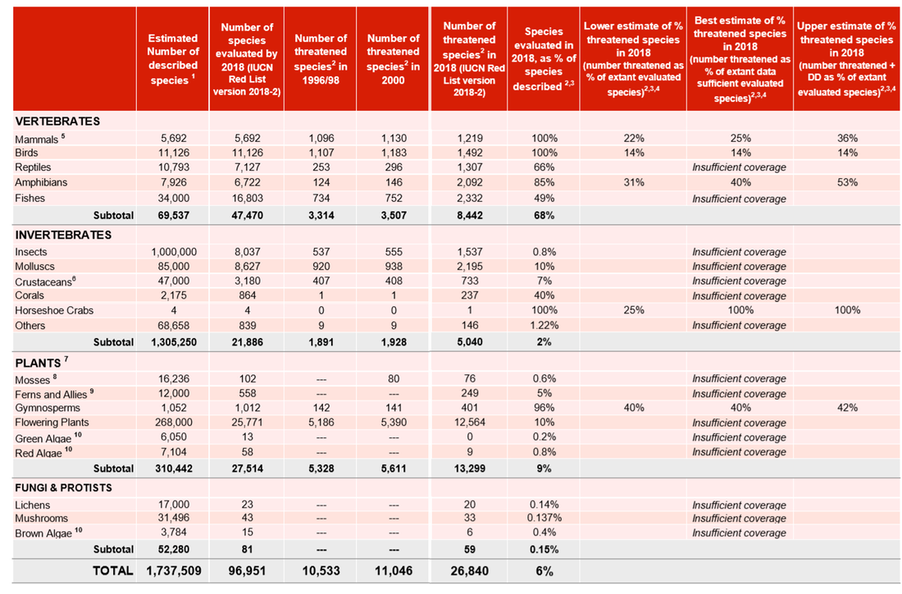

Our planet is now in the midst of its sixth mass extinction of plants and animals (Ceballos et al. 2015). We're currently experiencing the worst spate of species die-offs since the loss of the dinosaurs 65 million years ago. Although extinction is a natural phenomenon, it occurs at a natural “background” rate of about one to five species per year. Scientists estimate we're now losing species at 1,000 to 10,000 times the background rate, with literally dozens going extinct every day (De Vos et al. 2014). It could be a scary future indeed, with as many as 30 to 50 percent of all species possibly heading toward extinction by mid-century. 99 percent of currently threatened species are at risk from human activities, primarily those driving habitat loss, introduction of exotic species, and global warming. Because the rate of change in our biosphere is increasing, and because every species' extinction potentially leads to the extinction of others bound to that species in a complex ecological web, numbers of extinctions are likely to snowball in the coming decades as ecosystems unravel.

In the past 500 years, we know of approximately 1,000 species that have gone extinct, from the woodland bison of West Virginia and Arizona's Merriam's elk to the Rocky Mountain grasshopper, passenger pigeon and Puerto Rico's Culebra parrot — but this doesn't account for thousands of species that disappeared before scientists had a chance to describe them. Of roughly 1.5 million species that have been described another 8 million likely exist. So nobody really knows how many more species are in danger of becoming extinct. The IUCN has assessed roughly 3 percent of described species and identified 16,928 species worldwide as being threatened with extinction, or roughly 38 percent of those assessed. In its latest four-year endangered species assessment, the IUCN reports that the world isn't meeting our goal of reversing the extinction trend. Source: Center for Biological Diversity

Our planet is now in the midst of its sixth mass extinction of plants and animals (Ceballos et al. 2015). We're currently experiencing the worst spate of species die-offs since the loss of the dinosaurs 65 million years ago. Although extinction is a natural phenomenon, it occurs at a natural “background” rate of about one to five species per year. Scientists estimate we're now losing species at 1,000 to 10,000 times the background rate, with literally dozens going extinct every day (De Vos et al. 2014). It could be a scary future indeed, with as many as 30 to 50 percent of all species possibly heading toward extinction by mid-century. 99 percent of currently threatened species are at risk from human activities, primarily those driving habitat loss, introduction of exotic species, and global warming. Because the rate of change in our biosphere is increasing, and because every species' extinction potentially leads to the extinction of others bound to that species in a complex ecological web, numbers of extinctions are likely to snowball in the coming decades as ecosystems unravel.

In the past 500 years, we know of approximately 1,000 species that have gone extinct, from the woodland bison of West Virginia and Arizona's Merriam's elk to the Rocky Mountain grasshopper, passenger pigeon and Puerto Rico's Culebra parrot — but this doesn't account for thousands of species that disappeared before scientists had a chance to describe them. Of roughly 1.5 million species that have been described another 8 million likely exist. So nobody really knows how many more species are in danger of becoming extinct. The IUCN has assessed roughly 3 percent of described species and identified 16,928 species worldwide as being threatened with extinction, or roughly 38 percent of those assessed. In its latest four-year endangered species assessment, the IUCN reports that the world isn't meeting our goal of reversing the extinction trend. Source: Center for Biological Diversity

Threats to biodiversity can be summarized in the following main points:

Alteration and loss of the habitats

The transformation of the natural areas determines not only the loss of flora, but also a decrease in the animal species associated with them. One of the largest drivers of habitat loss in the tropics is palm oil, and can have a profound impact on wildlife.

Introduction of exotic species and genetically modified organisms

Species originating from a particular area, introduced into new natural environments can lead to different forms of imbalance in the ecological equilibrium.

Pollution

Human activity influences the natural environment producing negative, direct or indirect, effects that alter the flow of energy, the chemical and physical constitution of the environment and abundance of the species.

Climate change

Heating of the Earth’s surface affects biodiversity because it endangers all the species that are adapted to the cold (the Polar species) or the altitude (mountain species). With expanded droughts and excessive rainfall in certain areas, species are likely to be impacted directly or indirectly through factors like expanded vector ranges which can introduce infectious diseases.

In a potentially devastating web of interactions, climate change could wipe-out a third of parasites - making them one of the most threatened groups on the planet. This may sound wonderful until you realize that the loss of parasites could lead to complicated ecosystem break-downs. Species previously kept in check by parasitism would now be suddenly released from selection pressures and grow unabated, or unpredictable invasions of surviving parasites could break-free into new areas (Carlson et al. 2017).

Overexploitation of resources

When activities connected with capturing and harvesting (hunting, fishing, farming) a renewable natural resource in a particular area is excessively intense, the resource itself may become exhausted, as for example, is the case of sardines, herrings, cod, tuna and many other species that humans capture without leaving enough time for the organisms to reproduce.

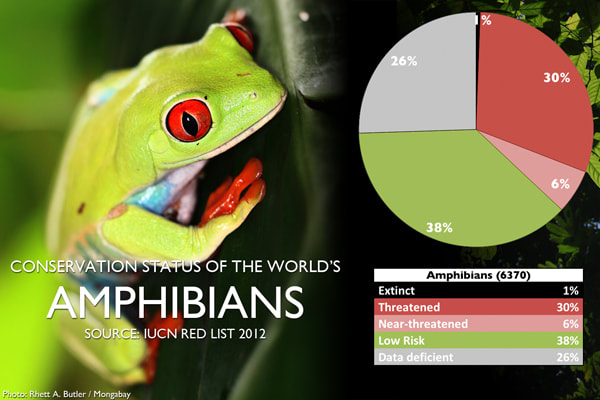

Certain groups are bound to be impacted more than others. No group of animals has a higher rate of endangerment than amphibians. Scientists estimate that a third or more of all the roughly 6,300 known species of amphibians are at risk of extinction. The current amphibian extinction rate may range from 25,039 to 45,474 times the background extinction rate. Frogs, toads, and salamanders are disappearing because of habitat loss, water and air pollution, climate change, ultraviolet light exposure, introduced exotic species, and disease. Because of their sensitivity to environmental changes, vanishing amphibians should be viewed as the canary in the global coal mine, signaling subtle yet radical ecosystem changes that could ultimately claim many other species, including humans.

Alteration and loss of the habitats

The transformation of the natural areas determines not only the loss of flora, but also a decrease in the animal species associated with them. One of the largest drivers of habitat loss in the tropics is palm oil, and can have a profound impact on wildlife.

Introduction of exotic species and genetically modified organisms

Species originating from a particular area, introduced into new natural environments can lead to different forms of imbalance in the ecological equilibrium.

Pollution

Human activity influences the natural environment producing negative, direct or indirect, effects that alter the flow of energy, the chemical and physical constitution of the environment and abundance of the species.

Climate change

Heating of the Earth’s surface affects biodiversity because it endangers all the species that are adapted to the cold (the Polar species) or the altitude (mountain species). With expanded droughts and excessive rainfall in certain areas, species are likely to be impacted directly or indirectly through factors like expanded vector ranges which can introduce infectious diseases.

In a potentially devastating web of interactions, climate change could wipe-out a third of parasites - making them one of the most threatened groups on the planet. This may sound wonderful until you realize that the loss of parasites could lead to complicated ecosystem break-downs. Species previously kept in check by parasitism would now be suddenly released from selection pressures and grow unabated, or unpredictable invasions of surviving parasites could break-free into new areas (Carlson et al. 2017).

Overexploitation of resources

When activities connected with capturing and harvesting (hunting, fishing, farming) a renewable natural resource in a particular area is excessively intense, the resource itself may become exhausted, as for example, is the case of sardines, herrings, cod, tuna and many other species that humans capture without leaving enough time for the organisms to reproduce.

Certain groups are bound to be impacted more than others. No group of animals has a higher rate of endangerment than amphibians. Scientists estimate that a third or more of all the roughly 6,300 known species of amphibians are at risk of extinction. The current amphibian extinction rate may range from 25,039 to 45,474 times the background extinction rate. Frogs, toads, and salamanders are disappearing because of habitat loss, water and air pollution, climate change, ultraviolet light exposure, introduced exotic species, and disease. Because of their sensitivity to environmental changes, vanishing amphibians should be viewed as the canary in the global coal mine, signaling subtle yet radical ecosystem changes that could ultimately claim many other species, including humans.

Birds occur in nearly every habitat on the planet and are often the most visible and familiar wildlife to people across the globe. As such, they provide an important indicator for tracking changes to the biosphere. Declining bird populations across most to all habitats confirm that profound changes are occurring on our planet in response to human activities.

A 2009 report on the state of birds in the United States found that 251 (31 percent) of the 800 species in the country are of conservation concern. Globally, BirdLife International estimates that 12 percent of known 9,865 bird species are now considered threatened, with 192 species, or 2 percent, facing an “extremely high risk” of extinction in the wild — two more species than in 2008. Habitat loss and degradation have caused most of the bird declines, but the impacts of invasive species and capture by collectors play a big role, too.

A 2009 report on the state of birds in the United States found that 251 (31 percent) of the 800 species in the country are of conservation concern. Globally, BirdLife International estimates that 12 percent of known 9,865 bird species are now considered threatened, with 192 species, or 2 percent, facing an “extremely high risk” of extinction in the wild — two more species than in 2008. Habitat loss and degradation have caused most of the bird declines, but the impacts of invasive species and capture by collectors play a big role, too.

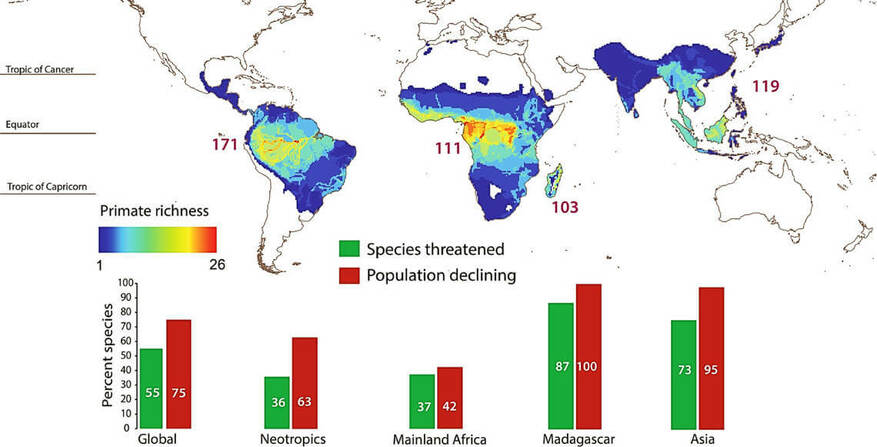

And perhaps one of the most striking elements of the present extinction crisis is the fact that the majority of our closest relatives — primates — are severely endangered. 60% of primate species are now threatened with extinction and ~75% have declining populations. Overall, the IUCN estimates that half the globe's 5,491 known mammals are declining in population and a fifth are clearly at risk of disappearing forever with no less than 1,131 mammals across the globe classified as endangered, threatened, or vulnerable.

A new study out, shows that just four countries - Brazil, Madagascar, Indonesia, and the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC)—harbor 65% of the world’s primate species (439) and 60% of these primates are Threatened, Endangered, or Critically Endangered (Estrada et al. 2018). Habitat

loss and fragmentation are main threats to primates in Brazil, Madagascar, and Indonesia. However, in DRC hunting for the commercial bushmeat trade is the primary threat. Encroachment on primate habitats driven by local and global market demands for food and non-food commodities hunting, illegal trade, the proliferation of invasive species, and human and domestic-animal borne infectious diseases cause habitat loss, population declines, and extirpation. Modeling agricultural expansion in the 21st century for the four countries under a worst case-scenario, showed a primate range contraction of 78% for Brazil, 72% for Indonesia, 62% for Madagascar, and 32% for DRC. Primates in Brazil and Madagascar have 38% of their range inside protected areas, 17% in Indonesia and 14% in DRC, suggesting that the great majority of primate populations remain vulnerable.

A new study out, shows that just four countries - Brazil, Madagascar, Indonesia, and the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC)—harbor 65% of the world’s primate species (439) and 60% of these primates are Threatened, Endangered, or Critically Endangered (Estrada et al. 2018). Habitat

loss and fragmentation are main threats to primates in Brazil, Madagascar, and Indonesia. However, in DRC hunting for the commercial bushmeat trade is the primary threat. Encroachment on primate habitats driven by local and global market demands for food and non-food commodities hunting, illegal trade, the proliferation of invasive species, and human and domestic-animal borne infectious diseases cause habitat loss, population declines, and extirpation. Modeling agricultural expansion in the 21st century for the four countries under a worst case-scenario, showed a primate range contraction of 78% for Brazil, 72% for Indonesia, 62% for Madagascar, and 32% for DRC. Primates in Brazil and Madagascar have 38% of their range inside protected areas, 17% in Indonesia and 14% in DRC, suggesting that the great majority of primate populations remain vulnerable.

Source: School Energy & Environment; Center for Biological Diversity; Sweetlove et al. 2011; Estrada et al. 2017

Vietnam has the highest number of primate taxa overall (24–27) and the highest number of globally threatened primate taxa (minimum 20) in Mainland Southeast Asia. As in other parts of Southeast Asia, Vietnam’s primates are threatened by hunting, both for subsistence and to supply the wildlife trade, and by forest degradation and fragmentation.

It's becoming increasingly clear that species extinctions themselves can be the cause of further extinctions, since species affect each

other through networks of ecological interactions. Simpler ecological communities are at greater risk of "run-away extinction cascades" with the potential loss of many species. See Trophic Redundancy Reduces Vulnerability to Extinction Cascades.

And, we should start considering the extinction crisis as an existential threat far exceeding the impacts of climate change. Yes, climate change will likely have devastating impacts on the planet, people and biodiversity; however, climate change can be mitigated whereas once biodiversity is lost, there is no way to resurrect the complexity and uniqueness of species, ecosystems, and landscapes.

So what is the solution to the extinction crisis? There is no single solution. Instead, there are many small grass-root and large governmental solutions that everyone can follow - and contribute to - now (Conservation Solutions). Maybe the most important step is to aside large protected areas - both on land and in water - that are minimally impacted by people. But first, learn more about what issues we currently face.

News

Nature crisis: Humans 'threaten 1m species with extinction'

All the Species That Went Extinct in 2018, and Ones on the Brink for 2019

The Rapid Decline Of The Natural World Is A Crisis Even Bigger Than Climate Change

12 signs we're in the middle of a 6th mass extinction

Sources

Estrada, A., Garber, P. A., Mittermeier, R. A., Wich, S., Gouveia, S., Dobrovolski, R., ... & Williamson, E. A. (2018). Primates in peril: the significance of Brazil, Madagascar, Indonesia and the Democratic Republic of the Congo for global primate conservation. PeerJ, 6.

Carlson, C. J., Burgio, K. R., Dougherty, E. R., Phillips, A. J., Bueno, V. M., Clements, C. F., ... & Doña, J. (2017). Parasite biodiversity faces extinction and redistribution in a changing climate. Science advances, 3(9), e1602422.

De Vos, J. M., Joppa, L. N., Gittleman, J. L., Stephens, P. R., & Pimm, S. L. (2015). Estimating the normal background rate of species extinction. Conservation biology, 29(2), 452-462.

Halley, J. M., Monokrousos, N., Mazaris, A. D., Newmark, W. D., & Vokou, D. (2016). Dynamics of extinction debt across five taxonomic groups. Nature Communications, 7, 12283.

Brook, B. W., Sodhi, N. S., & Bradshaw, C. J. (2008). Synergies among extinction drivers under global change. Trends in ecology & evolution, 23(8), 453-460.

Nature crisis: Humans 'threaten 1m species with extinction'

All the Species That Went Extinct in 2018, and Ones on the Brink for 2019

The Rapid Decline Of The Natural World Is A Crisis Even Bigger Than Climate Change

12 signs we're in the middle of a 6th mass extinction

Sources

Estrada, A., Garber, P. A., Mittermeier, R. A., Wich, S., Gouveia, S., Dobrovolski, R., ... & Williamson, E. A. (2018). Primates in peril: the significance of Brazil, Madagascar, Indonesia and the Democratic Republic of the Congo for global primate conservation. PeerJ, 6.

Carlson, C. J., Burgio, K. R., Dougherty, E. R., Phillips, A. J., Bueno, V. M., Clements, C. F., ... & Doña, J. (2017). Parasite biodiversity faces extinction and redistribution in a changing climate. Science advances, 3(9), e1602422.

De Vos, J. M., Joppa, L. N., Gittleman, J. L., Stephens, P. R., & Pimm, S. L. (2015). Estimating the normal background rate of species extinction. Conservation biology, 29(2), 452-462.

Halley, J. M., Monokrousos, N., Mazaris, A. D., Newmark, W. D., & Vokou, D. (2016). Dynamics of extinction debt across five taxonomic groups. Nature Communications, 7, 12283.

Brook, B. W., Sodhi, N. S., & Bradshaw, C. J. (2008). Synergies among extinction drivers under global change. Trends in ecology & evolution, 23(8), 453-460.

Nature’s Dangerous Decline ‘Unprecedented’; Species Extinction Rates ‘Accelerating’: IPBES

Scale of Loss of NatureGains from societal and policy responses, while important, have not stopped massive losses.

Since 1970, trends in agricultural production, fish harvest, bioenergy production and harvest of materials have increased, in response to population growth, rising demand and technological development, this has come at a steep price, which has been unequally distributed within and across countries. Many other key indicators of nature’s contributions to people however, such as soil organic carbon and pollinator diversity, have declined, indicating that gains in material contributions are often not sustainable .

The pace of agricultural expansion into intact ecosystems has varied from country to country. Losses of intact ecosystems have occurred primarily in the tropics, home to the highest levels of biodiversity on the planet. For example, 100 million hectares of tropical forest were lost from 1980 to 2000, resulting mainly from cattle ranching in Latin America (about 42 million hectares) and plantations in South-East Asia (about 7.5 million hectares, of which 80% is for palm oil, used mostly in food, cosmetics, cleaning products and fuel) among others.

Since 1970 the global human population has more than doubled (from 3.7 to 7.6 billion), rising unevenly across countries and regions; and per capita gross domestic product is four times higher – with ever-more distant consumers shifting the environmental burden of consumption and production across regions.

The average abundance of native species in most major land-based habitats has fallen by at least 20%, mostly since 1900.

The numbers of invasive alien species per country have risen by about 70% since 1970, across the 21 countries with detailed records.

The distributions of almost half (47%) of land-based flightless mammals, for example, and almost a quarter of threatened birds, may already have been negatively affected by climate change.

Indigenous Peoples, Local Communities and Nature

At least a quarter of the global land area is traditionally owned, managed, used or occupied by Indigenous Peoples. These areas include approximately 35% of the area that is formally protected, and approximately 35% of all remaining terrestrial areas with very low human intervention.

Nature managed by Indigenous Peoples and Local Communities is under increasing pressure but is generally declining less rapidly than in other lands – although 72% of local indicators developed and used by Indigenous Peoples and Local Communities show the deterioration of nature that underpins local livelihoods.

The areas of the world projected to experience significant negative effects from global changes in climate, biodiversity, ecosystem functions and nature’s contributions to people are also areas in which large concentrations of Indigenous Peoples and many of the world’s poorest communities reside.

Regional and global scenarios currently lack and would benefit from an explicit consideration of the views, perspectives and rights of Indigenous Peoples and Local Communities, their knowledge and understanding of large regions and ecosystems, and their desired future development pathways. Recognition of the knowledge, innovations and practices, institutions and values of Indigenous Peoples and Local Communities and their inclusion and participation in environmental governance often enhances their quality of life, as well as nature conservation, restoration and sustainable use. Their positive contributions to sustainability can be facilitated through national recognition of land tenure, access and resource rights in accordance with national legislation, the application of free, prior and informed consent, and improved collaboration, fair and equitable sharing of benefits arising from the use, and co-management arrangements with local communities.

Global Targets and Policy Scenarios

Past and ongoing rapid declines in biodiversity, ecosystem functions and many of nature’s contributions to people mean that most international societal and environmental goals, such as those embodied in the Aichi Biodiversity Targets and the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development will not be achieved based on current trajectories.

The authors of the Report examined six policy scenarios – very different ‘baskets’ of clustered policy options and approaches, including ‘Regional Competition’, ‘Business as Usual’ and ‘Global Sustainability’ - projecting the likely impacts on biodiversity and nature’s contributions to people of these pathways by 2050. They concluded that, except in scenarios that include transformative change, the negative trends in nature, ecosystem functions and in many of nature’s contributions to people will continue to 2050 and beyond due to the projected impacts of increasing land and sea use change, exploitation of organisms and climate change.

Policy Tools, Options and Exemplary Practices

Policy actions and societal initiatives are helping to raise awareness about the impact of consumption on nature, protecting local environments, promoting sustainable local economies and restoring degraded areas. Together with initiatives at various levels these have contributed to expanding and strengthening the current network of ecologically representative and well-connected protected area networks and other effective area-based conservation measures, the protection of watersheds and incentives and sanctions to reduce pollution .

The Report presents an illustrative list of possible actions and pathways for achieving them across locations, systems and scales, which will be most likely to support sustainability. Taking an integrated approach:

In agriculture, the Report emphasizes, among others: promoting good agricultural and agroecological practices; multifunctional landscape planning (which simultaneously provides food security, livelihood opportunities, maintenance of species and ecological functions) and cross-sectoral integrated management. It also points to the importance of deeper engagement of all actors throughout the food system (including producers, the public sector, civil society and consumers) and more integrated landscape and watershed management; conservation of the diversity of genes, varieties, cultivars, breeds, landraces and species; as well as approaches that empower consumers and producers through market transparency, improved distribution and localization (that revitalizes local economies), reformed supply chains and reduced food waste.

In marine systems, the Report highlights, among others: ecosystem-based approaches to fisheries management; spatial planning; effective quotas; marine protected areas; protecting and managing key marine biodiversity areas; reducing run- off pollution into oceans and working closely with producers and consumers.

In freshwater systems, policy options and actions include, among others: more inclusive water governance for collaborative water management and greater equity; better integration of water resource management and landscape planning across scales; promoting practices to reduce soil erosion, sedimentation and pollution run-off; increasing water storage; promoting investment in water projects with clear sustainability criteria; as well as addressing the fragmentation of many freshwater policies.

In urban areas, the Report highlights, among others: promotion of nature-based solutions; increasing access to urban services and a healthy urban environment for low-income communities; improving access to green spaces; sustainable production and consumption and ecological connectivity within urban spaces, particularly with native species.

Across all examples, the Report recognises the importance of including different value systems and diverse interests and worldviews in formulating policies and actions. This includes the full and effective participation of Indigenous Peoples and Local Communities in governance, the reform and development of incentive structures and ensuring that biodiversity considerations are prioritised across all key sector planning.

“We have already seen the first stirrings of actions and initiatives for transformative change, such as innovative policies by many countries, local authorities and businesses, but especially by young people worldwide,” said Sir Robert Watson. “From the young global shapers behind the #VoiceforthePlanet movement, to school strikes for climate, there is a groundswell of understanding that urgent action is needed if we are to secure anything approaching a sustainable future. The IPBES Global Assessment Report offers the best available expert evidence to help inform these decisions, policies and actions – and provides the scientific basis for the biodiversity framework and new decadal targets for biodiversity, to be decided in late 2020 in China, under the auspices of the UN Convention on Biological Diversity.”

By the Numbers – Key Statistics and Facts from the ReportGeneral

- Three-quarters of the land-based environment and about 66% of the marine environment have been significantly altered by human actions. On average these trends have been less severe or avoided in areas held or managed by Indigenous Peoples and Local Communities.

- More than a third of the world’s land surface and nearly 75% of freshwater resources are now devoted to crop or livestock production.

- The value of agricultural crop production has increased by about 300% since 1970, raw timber harvest has risen by 45% and approximately 60 billion tons of renewable and nonrenewable resources are now extracted globally every year – having nearly doubled since 1980.

- Land degradation has reduced the productivity of 23% of the global land surface, up to US$577 billion in annual global crops are at risk from pollinator loss and 100-300 million people are at increased risk of floods and hurricanes because of loss of coastal habitats and protection.

- In 2015, 33% of marine fish stocks were being harvested at unsustainable levels; 60% were maximally sustainably fished, with just 7% harvested at levels lower than what can be sustainably fished.

- Plastic pollution has increased tenfold since 1980, 300-400 million tons of heavy metals, solvents, toxic sludge and other wastes from industrial facilities are dumped annually into the world’s waters, and fertilizers entering coastal ecosystems have produced more than 400 ocean ‘dead zones’, totalling more than 245,000 km2 (591-595) - a combined area greater than that of the United Kingdom.

- Negative trends in nature will continue to 2050 and beyond in all of the policy scenarios explored in the Report, except those that include transformative change – due to the projected impacts of increasing land-use change, exploitation of organisms and climate change, although with significant differences between regions.

Scale of Loss of NatureGains from societal and policy responses, while important, have not stopped massive losses.

Since 1970, trends in agricultural production, fish harvest, bioenergy production and harvest of materials have increased, in response to population growth, rising demand and technological development, this has come at a steep price, which has been unequally distributed within and across countries. Many other key indicators of nature’s contributions to people however, such as soil organic carbon and pollinator diversity, have declined, indicating that gains in material contributions are often not sustainable .

The pace of agricultural expansion into intact ecosystems has varied from country to country. Losses of intact ecosystems have occurred primarily in the tropics, home to the highest levels of biodiversity on the planet. For example, 100 million hectares of tropical forest were lost from 1980 to 2000, resulting mainly from cattle ranching in Latin America (about 42 million hectares) and plantations in South-East Asia (about 7.5 million hectares, of which 80% is for palm oil, used mostly in food, cosmetics, cleaning products and fuel) among others.

Since 1970 the global human population has more than doubled (from 3.7 to 7.6 billion), rising unevenly across countries and regions; and per capita gross domestic product is four times higher – with ever-more distant consumers shifting the environmental burden of consumption and production across regions.

The average abundance of native species in most major land-based habitats has fallen by at least 20%, mostly since 1900.

The numbers of invasive alien species per country have risen by about 70% since 1970, across the 21 countries with detailed records.

The distributions of almost half (47%) of land-based flightless mammals, for example, and almost a quarter of threatened birds, may already have been negatively affected by climate change.

Indigenous Peoples, Local Communities and Nature

At least a quarter of the global land area is traditionally owned, managed, used or occupied by Indigenous Peoples. These areas include approximately 35% of the area that is formally protected, and approximately 35% of all remaining terrestrial areas with very low human intervention.

Nature managed by Indigenous Peoples and Local Communities is under increasing pressure but is generally declining less rapidly than in other lands – although 72% of local indicators developed and used by Indigenous Peoples and Local Communities show the deterioration of nature that underpins local livelihoods.

The areas of the world projected to experience significant negative effects from global changes in climate, biodiversity, ecosystem functions and nature’s contributions to people are also areas in which large concentrations of Indigenous Peoples and many of the world’s poorest communities reside.

Regional and global scenarios currently lack and would benefit from an explicit consideration of the views, perspectives and rights of Indigenous Peoples and Local Communities, their knowledge and understanding of large regions and ecosystems, and their desired future development pathways. Recognition of the knowledge, innovations and practices, institutions and values of Indigenous Peoples and Local Communities and their inclusion and participation in environmental governance often enhances their quality of life, as well as nature conservation, restoration and sustainable use. Their positive contributions to sustainability can be facilitated through national recognition of land tenure, access and resource rights in accordance with national legislation, the application of free, prior and informed consent, and improved collaboration, fair and equitable sharing of benefits arising from the use, and co-management arrangements with local communities.

Global Targets and Policy Scenarios

Past and ongoing rapid declines in biodiversity, ecosystem functions and many of nature’s contributions to people mean that most international societal and environmental goals, such as those embodied in the Aichi Biodiversity Targets and the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development will not be achieved based on current trajectories.

The authors of the Report examined six policy scenarios – very different ‘baskets’ of clustered policy options and approaches, including ‘Regional Competition’, ‘Business as Usual’ and ‘Global Sustainability’ - projecting the likely impacts on biodiversity and nature’s contributions to people of these pathways by 2050. They concluded that, except in scenarios that include transformative change, the negative trends in nature, ecosystem functions and in many of nature’s contributions to people will continue to 2050 and beyond due to the projected impacts of increasing land and sea use change, exploitation of organisms and climate change.

Policy Tools, Options and Exemplary Practices

Policy actions and societal initiatives are helping to raise awareness about the impact of consumption on nature, protecting local environments, promoting sustainable local economies and restoring degraded areas. Together with initiatives at various levels these have contributed to expanding and strengthening the current network of ecologically representative and well-connected protected area networks and other effective area-based conservation measures, the protection of watersheds and incentives and sanctions to reduce pollution .

The Report presents an illustrative list of possible actions and pathways for achieving them across locations, systems and scales, which will be most likely to support sustainability. Taking an integrated approach:

In agriculture, the Report emphasizes, among others: promoting good agricultural and agroecological practices; multifunctional landscape planning (which simultaneously provides food security, livelihood opportunities, maintenance of species and ecological functions) and cross-sectoral integrated management. It also points to the importance of deeper engagement of all actors throughout the food system (including producers, the public sector, civil society and consumers) and more integrated landscape and watershed management; conservation of the diversity of genes, varieties, cultivars, breeds, landraces and species; as well as approaches that empower consumers and producers through market transparency, improved distribution and localization (that revitalizes local economies), reformed supply chains and reduced food waste.

In marine systems, the Report highlights, among others: ecosystem-based approaches to fisheries management; spatial planning; effective quotas; marine protected areas; protecting and managing key marine biodiversity areas; reducing run- off pollution into oceans and working closely with producers and consumers.

In freshwater systems, policy options and actions include, among others: more inclusive water governance for collaborative water management and greater equity; better integration of water resource management and landscape planning across scales; promoting practices to reduce soil erosion, sedimentation and pollution run-off; increasing water storage; promoting investment in water projects with clear sustainability criteria; as well as addressing the fragmentation of many freshwater policies.

In urban areas, the Report highlights, among others: promotion of nature-based solutions; increasing access to urban services and a healthy urban environment for low-income communities; improving access to green spaces; sustainable production and consumption and ecological connectivity within urban spaces, particularly with native species.

Across all examples, the Report recognises the importance of including different value systems and diverse interests and worldviews in formulating policies and actions. This includes the full and effective participation of Indigenous Peoples and Local Communities in governance, the reform and development of incentive structures and ensuring that biodiversity considerations are prioritised across all key sector planning.

“We have already seen the first stirrings of actions and initiatives for transformative change, such as innovative policies by many countries, local authorities and businesses, but especially by young people worldwide,” said Sir Robert Watson. “From the young global shapers behind the #VoiceforthePlanet movement, to school strikes for climate, there is a groundswell of understanding that urgent action is needed if we are to secure anything approaching a sustainable future. The IPBES Global Assessment Report offers the best available expert evidence to help inform these decisions, policies and actions – and provides the scientific basis for the biodiversity framework and new decadal targets for biodiversity, to be decided in late 2020 in China, under the auspices of the UN Convention on Biological Diversity.”

By the Numbers – Key Statistics and Facts from the ReportGeneral

- 75%: terrestrial environment “severely altered” to date by human actions (marine environments 66%)

- 47%: reduction in global indicators of ecosystem extent and condition against their estimated natural baselines, with many continuing to decline by at least 4% per decade

- 28%: global land area held and/or managed by Indigenous Peoples , including >40% of formally protected areas and 37% of all remaining terrestrial areas with very low human intervention

- +/-60 billion: tons of renewable and non-renewable resources extracted globally each year, up nearly 100% since 1980

- 15%: increase in global per capita consumption of materials since 1980

- >85%: of wetlands present in 1700 had been lost by 2000 – loss of wetlands is currently three times faster, in percentage terms, than forest loss.

- 8 million: total estimated number of animal and plant species on Earth (including 5.5 million insect species)

- Tens to hundreds of times: the extent to which the current rate of global species extinction is higher compared to average over the last 10 million years, and the rate is accelerating

- Up to 1 million: species threatened with extinction, many within decades

- >500,000 (+/-9%): share of the world’s estimated 5.9 million terrestrial species with insufficient habitat for long term survival without habitat restoration

- >40%: amphibian species threatened with extinction

- Almost 33%: reef forming corals, sharks and shark relatives, and >33% marine mammals threatened with extinction

- 25%: average proportion of species threatened with extinction across terrestrial, freshwater and marine vertebrate, invertebrate and plant groups that have been studied in sufficient detail

- At least 680: vertebrate species driven to extinction by human actions since the 16th century

- +/-10%: tentative estimate of proportion of insect species threatened with extinction

- >20%: decline in average abundance of native species in most major terrestrial biomes, mostly since 1900

+/-560 (+/-10%): domesticated breeds of mammals were extinct by 2016, with at least 1,000 more threatened - 3.5%: domesticated breed of birds extinct by 2016

- 70%: increase since 1970 in numbers of invasive alien species across 21 countries with detailed records

- 30%: reduction in global terrestrial habitat integrity caused by habitat loss and deterioration

- 47%: proportion of terrestrial flightless mammals and 23% of threatened birds whose distributions may have been negatively impacted by climate change already

- >6: species of ungulate (hoofed mammals) would likely be extinct or surviving only in captivity today without conservation measures

- 300%: increase in food crop production since 1970

- 23%: land areas that have seen a reduction in productivity due to land degradation

- >75%: global food crop types that rely on animal pollination

- US$235 to US$577 billion: annual value of global crop output at risk due to pollinator loss

- 5.6 gigatons: annual CO2 emissions sequestered in marine and terrestrial ecosystems – equivalent to 60% of global fossil fuel emission

- +/-11%: world population that is undernourished

- 100 million: hectares of agricultural expansion in the tropics from 1980 to 2000, mainly cattle ranching in Latin America (+/-42 million ha), and plantations in Southeast Asia (+/-7.5 million ha, of which 80% is oil palm), half of it at the expense of intact forests

- 3%: increase in land transformation to agriculture between 1992 and 2015, mostly at the expense of orests

- >33%: world’s land surface (and +/-75% of freshwater resources) devoted to crop or livestock production

- 12%: world’s ice-free land used for crop production

- 25%: world’s ice-free land used for grazing (+/-70% of drylands)

- +/-25%: greenhouse gas emissions caused by land clearing, crop production and fertilization, with animal-based food contributing 75% to that figure

- +/-30%: global crop production and global food supply provided by small land holdings (<2 ha), using +/-25% of agricultural land, usually maintaining rich agrobiodiversity

- $100 billion: estimated level of financial support in OECD countries (2015) to agriculture that is potentially harmful to the environment

- 33%: marine fish stocks in 2015 being harvested at unsustainable levels; 60% are maximally sustainably fished; 7% are underfished

- >55%: ocean area covered by industrial fishing

- 3-10%: projected decrease in ocean net primary production due to climate change alone by the end of the century

- 3-25%: projected decrease in fish biomass by the end of the century in low and high climate warming scenarios, respectively

- >90%: proportion of the global commercial fishers accounted for by small scale fisheries (over 30 million people) – representing nearly 50% of global fish catch

- Up to 33%: estimated share in 2011 of world’s reported fish catch that is illegal, unreported or unregulated

- >10%: decrease per decade in the extent of seagrass meadows from 1970-2000

- +/-50%: live coral cover of reefs lost since 1870s

- 100-300 million: people in coastal areas at increased risk due to loss of coastal habitat protection

- 400: low oxygen (hypoxic) coastal ecosystem ‘dead zones’ caused by fertilizers, affecting >245,000 km2

- 29%: average reduction in the extinction risk for mammals and birds in 109 countries thanks to conservation investments from 1996 to 2008; the extinction risk of birds, mammals and amphibians would have been at least 20% greater without conservation action in recent decade

- >107: highly threatened birds, mammals and reptiles estimated to have benefitted from the eradication of invasive mammals on islands

- 45%: increase in raw timber production since 1970 (4 billion cubic meters in 2017)

- +/-13 million: forestry industry jobs

- 50%: agricultural expansion that occurred at the expense of forests

- 50%: decrease in net rate of forest loss since the 1990s (excluding those managed for timber or agricultural extraction)

- 68%: global forest area today compared with the estimated pre-industrial level

- 7%: reduction of intact forests (>500 sq. km with no human pressure) from 2000-2013 in developed and developing countries

- 290 million ha (+/-6%): native forest cover lost from 1990-2015 due to clearing and wood harvesting

- 110 million ha: rise in the area of planted forests from 1990-2015

- 10-15%: global timber supplies provided by illegal forestry (up to 50% in some areas)

- >2 billion: people who rely on wood fuel to meet their primary energy needs

- <1%: total land used for mining, but the industry has significant negative impacts on biodiversity, emissions, water quality and human health

- +/-17,000: large-scale mining sites (in 171 countries), mostly managed by 616 international corporations

- +/-6,500: offshore oil and gas ocean mining installations ((in 53 countries)

- US$345 billion: global subsidies for fossil fuels resulting in US$5 trillion in overall costs, including nature deterioration externalities; coal accounts for 52% of post-tax subsidies, petroleum for +/-33% and natural gas for +/-10%

- >100%: growth of urban areas since 1992

- 25 million km: length of new paved roads foreseen by 2050, with 90% of construction in least developed and developing countries

- +/-50,000: number of large dams (>15m height) ; +/-17 million reservoirs (>0.01 ha)

- 105%: increase in global human population (from 3.7 to 7.6 billion) since 1970 unevenly across countries and regions

- 50 times higher: per capita GDP in developed vs. least developed countries

- >2,500: conflicts over fossil fuels, water, food and land currently occurring worldwide

- >1,000: environmental activists and journalists killed between 2002 and 2013

- 70%: proportion of cancer drugs that are natural or synthetic products inspired by nature

- +/-4 billion: people who rely primarily on natural medicines

- 17%: infectious diseases spread by animal vectors, causing >700,000 annual deaths

- +/-821 million: people face food insecurity in Asia and Africa

- 40%: of the global population lacks access to clean and safe drinking water

- >80%: global wastewater discharged untreated into the environment

- 300-400 million tons: heavy metals, solvents, toxic sludge, and other wastes from industrial facilities dumped annually into the world’s waters

- 10 times: increase in plastic pollution since 1980

- 1 degree Celsius: average global temperature difference in 2017 compared to pre-industrial levels, rising +/-0.2 (+/-0.1) degrees Celsius per decade

- >3 mm: annual average global sea level rise over the past two decades

- 16-21 cm: rise in global average sea level since 1900

- 100% increase since 1980 in greenhouse gas emissions, raising average global temperature by at least 0.7 degree

- 40%: rise in carbon footprint of tourism (to 4.5Gt of carbon dioxide) from 2009 to 2013

- 8%: of total greenhouse gas emissions are from transport and food consumption related to tourism

- 5%: estimated fraction of species at risk of extinction from 2°C warming alone, rising to 16% at 4.3°C warming

- Even for global warming of 1.5 to 2 degrees, the majority of terrestrial species ranges are projected to shrink profoundly.

- Most: Aichi Biodiversity Targets for 2020 likely to be missed

- 22 of 44: assessed targets under the Sustainable Development Goals related to poverty, hunger, health, water, cities, climate, ocean and land are being undermined by substantial negative trends in nature and its contributions to people

- 72%: of local indicators in nature developed and used by Indigenous Peoples and Local Communities that show negative trends

- 4: number of Aichi Targets where good progress has been made on certain components, with moderate progress on some components of another 7 targets, poor progress on all components of 6 targets, and insufficient information to assess progress on some or all components of the remaining 3 targets