It is estimated that deforestation and forest degradation may account for up to 25% of global carbon emissions. Even the most conservative estimates put the figure at 15%. Either way, this represents a significant contribution to global warming and, as such, warrants close attention in any serious discussions on the most effective ways to minimize the impacts of climate change.

The concept of REDD+ creates a financial value for the carbon stored in forests by offering incentives for developing countries to avoid emissions and invest in low-carbon paths to sustainable development – rewarding them for keeping their forests intact, in other words. REDD+ gives forests a dollar value based on how much carbon they contain, and the money generated from the sale of so-called carbon credits (basically, permits to emit a defined amount of carbon) is reinvested in the communities that have elected not to destroy their forests. This has the double benefit of preventing the release of more so-called greenhouse gases while simultaneously safeguarding the forest biodiversity and ecosystem services on which local communities – and ultimately all of us – depend for survival.

REDD+ is being developed through a combination of top-down (jurisdictional) approaches, spearheaded by the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change and the national governments that have signed up to the treaty, allied with bottom-up, project-based initiatives that focus on forest areas under threat. Top-down or jurisdictional approaches to REDD+ architecture need to be matched against grounded lessons from real world projects around the globe; both levels are critical for REDD+ to be effective. Unfortunately, not all REDD+ projects place an emphasis on biodiversity, and this is a major flaw.

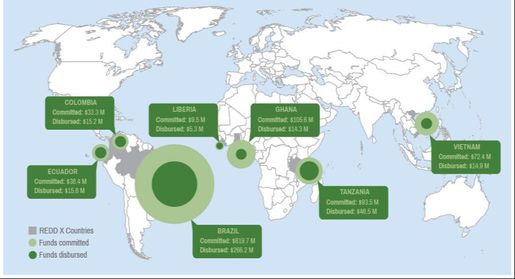

Source: Fauna & Flora International

The concept of REDD+ creates a financial value for the carbon stored in forests by offering incentives for developing countries to avoid emissions and invest in low-carbon paths to sustainable development – rewarding them for keeping their forests intact, in other words. REDD+ gives forests a dollar value based on how much carbon they contain, and the money generated from the sale of so-called carbon credits (basically, permits to emit a defined amount of carbon) is reinvested in the communities that have elected not to destroy their forests. This has the double benefit of preventing the release of more so-called greenhouse gases while simultaneously safeguarding the forest biodiversity and ecosystem services on which local communities – and ultimately all of us – depend for survival.

REDD+ is being developed through a combination of top-down (jurisdictional) approaches, spearheaded by the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change and the national governments that have signed up to the treaty, allied with bottom-up, project-based initiatives that focus on forest areas under threat. Top-down or jurisdictional approaches to REDD+ architecture need to be matched against grounded lessons from real world projects around the globe; both levels are critical for REDD+ to be effective. Unfortunately, not all REDD+ projects place an emphasis on biodiversity, and this is a major flaw.

Source: Fauna & Flora International