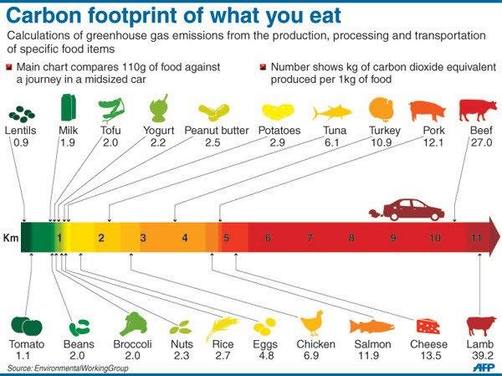

A relatively easy way to reduce your impact on the planet, and reduce your carbon footprint, is to switch to a plant-based diet, or at the very least stop eating red meat. For those from developed countries, small changes can make a huge difference. The highest total of livestock-related greenhouse-gas emissions comes from the developing world, which accounts for 75% of the global emissions from cattle and other ruminants and 56% of the global emissions from poultry and pigs. There may be no other single human activity that has a bigger impact on the planet than the raising of livestock. Some 40% of the world’s land surface is used for the purposes of keeping all 7 billion of us fed — albeit some of us, of course, more than others. Of the 95 million tons of beef produced in the world in 2000, the vast majority came from cattle in Latin America, Europe and North America. Meat production is the single largest reason for rainforest destruction. Global transition toward low-meat diets could reduce the costs of climate change mitigation by as much as 50 percent by 2050. At the very least, stop eating red meat. Why? The most climate-friendly meats comes from pigs and poultry, which account for only 10% of total livestock greenhouse-gas emissions while contributing more than three times as much meat globally as cattle. Pork and poultry are also more efficient for feed, requiring up to five times less feed to produce a kg of protein than a cow, a sheep or a goat.

Other reasons to switch to a planet-based diet: 1) healthier and longer-lived lives, 2) conserve precious water, 3) cut your carbon footprint, 4) save precious wildlife habitats, 5) reduce water pollution from agricultural run-off, and 6) cleaner air from reduced emissions from livestock.

Why does it matter? Demand for animal protein is growing. Global consumption of meat is forecast to increase 76 per cent on recent levels by mid-century. A ‘protein transition’ is playing out across the developing world: as incomes rise, consumption of meat is increasing. In the developed world, per capita demand for meat has reached a plateau, but at excessive levels. Among industrialized countries, the average person consumes around twice as much as experts deem healthy. In the United States, the multiple is nearly three times.

This is not sustainable. A growing global population cannot converge on developed-country levels of meat consumption without huge social and environmental cost. Overconsumption of animal products, in particular processed meat, is associated with obesity and an

increased risk of non-communicable diseases (NCDs) such as heart disease, type-2 diabetes and certain types of cancer. Livestock production is often a highly inefficient use of scarce land and water. It is a principal driver of deforestation, habitat destruction and species loss.

Crucially, these consumption trends are incompatible with the objective of avoiding dangerous climate change. The livestock sector is already responsible for just under 15 per cent of the global total, and equivalent to tailpipe emissions from all the world’s vehicles. Rising demand means emissions will continue to rise. Even with best efforts to reduce the emissions footprint of livestock production, the sector will consume a growing share of the remaining carbon budget. This will make it extremely difficult to realize the goal of limiting the average global temperature rise to 2°C above pre-industrial levels, agreed in 2010 by parties to the UN climate change conference in Cancún.

There remains a significant gap between the emissions reductions countries have proposed and what is required for a decent chance of keeping temperature rise below 2°C. Governments need credible strategies to close the gap, and reducing meat consumption is an obvious one: worldwide adoption of a healthy diet would generate over a quarter of the emission reductions needed by 2050.

There is therefore a compelling case for shifting diets, and above all for addressing meat consumption. However, governments are trapped in a cycle of inertia: they fear the repercussions of intervention, while low public awareness means they feel no pressure to intervene.

Key findings

Governments must lead

Governments are the only actors with the necessary resources and capacities to redirect diets at scale towards more sustainable, plant-based sources of protein.

• The market is failing. Without government intervention at national and international level, populations are unlikely to reduce their consumption of animal products and there is insufficient incentive for business to reduce supply. Global overconsumption will bring increasing costs for society and the environment.

• Publics expect government leadership. Focus groups conducted during the research across four countries with varying political, economic and cultural conditions all demonstrated a general belief that it is the role of government to spearhead efforts to address unsustainable consumption of meat. Government inaction signals to publics that the issue is unimportant or undeserving of concern.

• Governments overestimate the risk of public backlash. Soft interventions to raise awareness among consumers or ‘nudge’ them towards more sustainable choices, for example by increasing the availability and prominence of alternative options at the point of sale, are likely to be well received. More interventionist – but necessary – approaches such as taxation do risk public resistance, but focus

group respondents thought this would be short-lived, particularly if people understood the policy rationale.

Public understanding of livestock’s role in climate change is low relative to that for comparable sources of emissions. People have generally not read or heard about the connection, and may struggle to reconcile it with their own understanding of how emissions occur.

• The impact of increased awareness on behaviour is intricate. Increased understanding of the link between livestock and climate change is associated with greater willingness to reduce consumption. At the point of purchase, however, more immediate considerations – both conscious and subconscious – have more sway over consumer decisions. Price, health and food safety have the greatest bearing on

food choices, while subconscious cues offered by the marketing environment influence an individual’s automatic decision-making. Consequently, strategies focused only on raising awareness will not result in societal behaviour change.

• Raising awareness can bolster support for government action. Although raising awareness is unlikely to have a marked impact on individual behaviour, it may make the public more supportive and accepting of policy intervention. Focus group discussions revealed that people were more likely to back government action after being exposed to information about the role of livestock in climate change. Public information campaigns were perceived as a necessary first step in any wider strategy to reduce consumption.\

Emissions vary by animal and production system. Broadly speaking, emissions from ruminant animals – cows, sheep and goats – are higher than for animals such as chickens or pigs, and emissions from animal products more generally are considerably higher than those associated with plant-based foods. However, significant variation can result from differences in production system and life-cycle

assessment methodologies.

• Trade-offs abound. What is best for the climate may not be best for animals or other aspects of the environment. For example, emissions from intensively reared beef tend to be lower than from pasture-fed beef, but the practice raises other problems relating to

animal welfare, inefficient use of crops for feed, water pollution and antimicrobial resistance from overuse of antibiotics. The picture is complex.

• The risk of confusion is high. Complexity presents an opportunity for interest groups to cloud the issue and create doubt or uncertainty in the minds of consumers, for example by conflating direct and life-cycle emissions or blaming the problem on unsustainable production practices in other countries.

• However, the overall message is clear: globally we should eat less meat. Global per capita meat consumption is already above healthy levels; critically so in developed countries. We cannot avoid dangerous climate change unless consumption trends change.

Source: Changing Climate, Changing Diets Pathways to Lower Meat Consumption

Additional reading

To feed its own people, Brazil embarks on long road to turn its back on intensive agriculture

The Triple Whopper Environmental Impact of Global Meat Production

People Still Don't Get the Link between Meat Consumption and Climate Change

Why Farmers Can Prevent Global Warming Just As Well As Vegetarians

5 Ways Eating More Plant-Based Foods Benefits the Environment

Why does it matter? Demand for animal protein is growing. Global consumption of meat is forecast to increase 76 per cent on recent levels by mid-century. A ‘protein transition’ is playing out across the developing world: as incomes rise, consumption of meat is increasing. In the developed world, per capita demand for meat has reached a plateau, but at excessive levels. Among industrialized countries, the average person consumes around twice as much as experts deem healthy. In the United States, the multiple is nearly three times.

This is not sustainable. A growing global population cannot converge on developed-country levels of meat consumption without huge social and environmental cost. Overconsumption of animal products, in particular processed meat, is associated with obesity and an

increased risk of non-communicable diseases (NCDs) such as heart disease, type-2 diabetes and certain types of cancer. Livestock production is often a highly inefficient use of scarce land and water. It is a principal driver of deforestation, habitat destruction and species loss.

Crucially, these consumption trends are incompatible with the objective of avoiding dangerous climate change. The livestock sector is already responsible for just under 15 per cent of the global total, and equivalent to tailpipe emissions from all the world’s vehicles. Rising demand means emissions will continue to rise. Even with best efforts to reduce the emissions footprint of livestock production, the sector will consume a growing share of the remaining carbon budget. This will make it extremely difficult to realize the goal of limiting the average global temperature rise to 2°C above pre-industrial levels, agreed in 2010 by parties to the UN climate change conference in Cancún.

There remains a significant gap between the emissions reductions countries have proposed and what is required for a decent chance of keeping temperature rise below 2°C. Governments need credible strategies to close the gap, and reducing meat consumption is an obvious one: worldwide adoption of a healthy diet would generate over a quarter of the emission reductions needed by 2050.

There is therefore a compelling case for shifting diets, and above all for addressing meat consumption. However, governments are trapped in a cycle of inertia: they fear the repercussions of intervention, while low public awareness means they feel no pressure to intervene.

Key findings

Governments must lead

Governments are the only actors with the necessary resources and capacities to redirect diets at scale towards more sustainable, plant-based sources of protein.

• The market is failing. Without government intervention at national and international level, populations are unlikely to reduce their consumption of animal products and there is insufficient incentive for business to reduce supply. Global overconsumption will bring increasing costs for society and the environment.

• Publics expect government leadership. Focus groups conducted during the research across four countries with varying political, economic and cultural conditions all demonstrated a general belief that it is the role of government to spearhead efforts to address unsustainable consumption of meat. Government inaction signals to publics that the issue is unimportant or undeserving of concern.

• Governments overestimate the risk of public backlash. Soft interventions to raise awareness among consumers or ‘nudge’ them towards more sustainable choices, for example by increasing the availability and prominence of alternative options at the point of sale, are likely to be well received. More interventionist – but necessary – approaches such as taxation do risk public resistance, but focus

group respondents thought this would be short-lived, particularly if people understood the policy rationale.

Public understanding of livestock’s role in climate change is low relative to that for comparable sources of emissions. People have generally not read or heard about the connection, and may struggle to reconcile it with their own understanding of how emissions occur.

• The impact of increased awareness on behaviour is intricate. Increased understanding of the link between livestock and climate change is associated with greater willingness to reduce consumption. At the point of purchase, however, more immediate considerations – both conscious and subconscious – have more sway over consumer decisions. Price, health and food safety have the greatest bearing on

food choices, while subconscious cues offered by the marketing environment influence an individual’s automatic decision-making. Consequently, strategies focused only on raising awareness will not result in societal behaviour change.

• Raising awareness can bolster support for government action. Although raising awareness is unlikely to have a marked impact on individual behaviour, it may make the public more supportive and accepting of policy intervention. Focus group discussions revealed that people were more likely to back government action after being exposed to information about the role of livestock in climate change. Public information campaigns were perceived as a necessary first step in any wider strategy to reduce consumption.\

Emissions vary by animal and production system. Broadly speaking, emissions from ruminant animals – cows, sheep and goats – are higher than for animals such as chickens or pigs, and emissions from animal products more generally are considerably higher than those associated with plant-based foods. However, significant variation can result from differences in production system and life-cycle

assessment methodologies.

• Trade-offs abound. What is best for the climate may not be best for animals or other aspects of the environment. For example, emissions from intensively reared beef tend to be lower than from pasture-fed beef, but the practice raises other problems relating to

animal welfare, inefficient use of crops for feed, water pollution and antimicrobial resistance from overuse of antibiotics. The picture is complex.

• The risk of confusion is high. Complexity presents an opportunity for interest groups to cloud the issue and create doubt or uncertainty in the minds of consumers, for example by conflating direct and life-cycle emissions or blaming the problem on unsustainable production practices in other countries.

• However, the overall message is clear: globally we should eat less meat. Global per capita meat consumption is already above healthy levels; critically so in developed countries. We cannot avoid dangerous climate change unless consumption trends change.

Source: Changing Climate, Changing Diets Pathways to Lower Meat Consumption

Additional reading

To feed its own people, Brazil embarks on long road to turn its back on intensive agriculture

- Brazil a signatory to COP28 Declaration on Sustainable Agriculture, Resilient Food Systems and Climate Action

- Intensive agriculture a barrier with handful of companies dominating fourth largest global food producer

- Family farming produces 70% of population's food but occupies just 23% of Brazil's arable area

- NGOs and startups working with communities to increase diversity of food and supply resilience

- Putting 1.02m hectares of deforested areas to agroforestry could produce 156m tons food and remove CO2

- Collecting data from the last 40 years, researchers have observed increased temperatures and more severe droughts in the Matopiba region, which encompasses parts of Maranhão, Tocantins, Piauí and Bahia states.

- A transition zone between the Cerrado and the eastern Amazon, the Matopiba is the largest area of contact between forest and savanna in the tropics; in the last two decades it has become one of the main fronts for the expansion of grain cultivation in Brazil.

- According to the researchers, the increased frequency of hot and dry days in the region results from an interaction between global climate change and the advance of deforestation.

- In the near future, environmental changes can harm agribusiness itself, putting Brazilian food security at risk.

The Triple Whopper Environmental Impact of Global Meat Production

People Still Don't Get the Link between Meat Consumption and Climate Change

Why Farmers Can Prevent Global Warming Just As Well As Vegetarians

5 Ways Eating More Plant-Based Foods Benefits the Environment